|

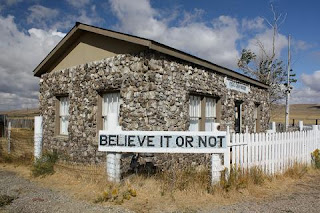

| Fossil Cabin on Lincoln Highway, southeast Wyoming, USA. |

|

| Fossil collecting in the olden days, southeast Wyoming. |

|

| Courtesy Stegosaurus On-Line. |

During the late Jurassic, ca 155 to 145 million years ago, the landscape in "southeast Wyoming" was very different from the sagebrush grasslands of today. The supercontinent Laurasia had split in two, and North America was moving north through subtropical latitudes. The environment was semi-arid, with lush vegetation in swampy lowlands and along rivers, dominated by conifers, ginkgos, cycads, tree ferns and horsetails. The abundant dinosaurs probably lived in riparian zones and near wetlands. Herbivorous sauropods were common -- quadrapedal giants with long necks and tails. There were armored dinosaurs such as Stegosaurus, and bipedal carnivores such as Allosaurus. Lungfishes, frogs, turtles, lizards, pterosaurs and early mammals were present as well.

This vast lowland, perhaps as much as 1.5 million sq km (600,000 sq mi) in extent, formed when precursors of the Rocky Mountains rose to the west. Streams running off the uplands for some ten million years filled the basin with sands, silts and clays, mixed with the abundant bones of the residents. The resulting sedimentary rocks eventually would be exposed with uplift of the Rocky Mountains -- the sandstones, siltstones, mudstones and fresh-water limestones of the “uniformly variable” Morrison Formation. The Morrison often is easy to recognize, with its variegated outcrops ranging from light grey to greenish gray to red to almost purple. Multiple beds are fossiliferous, some extremely and famously so.

|

| Variegated beds of the Morrison. Photo by Geotripper. |

The Anticline

North of the bone house, the land slopes gradually up to a ridge crest several hundred feet above the highway. This is Como Bluff, a small anticline at the northern edge of the Laramie Basin. It was uplifted during the Laramide Orogeny, the mountain-building event that created much of the Rocky Mountains beginning about 80 million years ago.

|

| Como Bluff anticline east of Medicine Bow. Courtesy Google Earth, click to view. |

The Como Bluff anticline is an east-west trending ridge about ten miles long that plunges to the west; the axis (crest) meets the Lincoln Highway four miles east of the town of Medicine Bow. The anticline is highly asymmetric. The south side dips gently southward, reflected in the gradual slope behind the house. The uplift is bounded on the northwest by a high-angle reverse fault, with strata vertical to overturned in places. The asymmetry has created a sandstone hogback with exposures of the Morrison Formation on the inner face -- the backside of the ridge above the house. These are the actual bluffs of Como Bluff.

The Discovery

In 1876, Como Bluff was the site of one of the biggest fossil finds in North America. The original discovery was made by William Harlow Reed and William Edwards Carlin, station agent and station foreman at the Union Pacific Railroad’s Como Station in Wyoming Territory. Many locals were aware of the abundant fossilized bones, but apparently Reed and Carlin knew enough to recognize their importance. They even identified some to species -- Megatherum, a giant ice age sloth. Reed and Carlin wrote a letter to Professor Marsh describing their finds; several months later Marsh received a package containing a shoulder blade and vertebra from the giant sloth. He immediately recognized both the true identity of the bones (the sauropod Brontosaurus) and the value of the material. It was at that point that he directed his field assistant Williston to make a trip to Wyoming Territory to assess the merit of the site. The story from there has been told many times -- of the Dinosaur Graveyard, the Bone Wars and the two opposing gladiators, Othneil Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope (several accounts listed at end of post).

|

| Stegosaurus cast, Geology Museum, University of Wyoming. From specimen at the American Museum of Natural History, found near Como Bluff in1994. |

Reed and Carlin continued as employees of the Union Pacific, but also worked on Marsh’s field crews. Carlin switched sides, going to work for Cope before giving up the fossil business altogether. Reed stayed with Marsh, eventually becoming a full time fossil collector. He went on to work for prominent institutions such as the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History. Reed was appointed Curator of the Geological Museum and Geology Instructor at the University of Wyoming, where he stayed until his death in 1915.

|

| W.H. Reed in the Bone Room, early 1900s. Miscellaneous AHC Collections. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission. |

By 1932, a steady stream of travelers was crossing Wyoming on the Lincoln Highway. Popular stops in the eastern part of the state included the old Texas Trail in Pine Bluffs, the historic Union Pacific Railroad Depot in Cheyenne, the University Museum in Laramie and the Virginian Hotel in Medicine Bow. East of Medicine Bow, homesteader Thomas Boylan had been gathering bones at Como Bluff, planning to reconstruct dinosaur skeletons along the highway as a tourist attraction. But a specialist from the University of Wyoming quashed the plans when he explained that the 5796 bones were such a mix of species that there was no hope of putting together even a single dinosaur. Instead Boylan built a house by the side of the road, a dinosaur museum called the Fossil Cabin.

|

| Como Bluff Museum postcard, 1938. Ludwig-Svenson Studio Collection. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission |

Boylan and his wife, Grayce, did a booming business with their museum and service station, especially after Ripley’s Believe It or Not featured the “Oldest House in the World” in newspapers around the country in 1938. Their business thrived even during the Depression and World War II. The Lincoln Highway was the main east-west thoroughfare across the United States, and traffic increased steadily through the 1960s.

|

| Lincoln Highway, from "Historic Motor Convoy Treks the Lincoln Highway." No source given. |

Then in 1970, Interstate Highway 80 between Laramie and Rawlins was completed, turning the Lincoln Highway into a back road. Tourist business dropped off dramatically, and Grayce Boylan finally sold the cabin in 1974. The new owners continued to operate the museum until 1992. As of 2011, the museum was closed and the property for sale. [For status updates, check with the town of Medicine Bow.]

Visiting Como Bluff and the little bone house on the prairie

|

| Photo from wyominghistory.com. |

The Morrison Formation lies just over the hill to the north, but is not accessible from the cabin due to private ownership. For views of the famous outcrops, take Albany County Road 610, the Marshall Road, north from US 30. This turnoff is about 9 miles east of Medicine Bow and 5 miles west of Rock River, marked by a sign for the Como Bluff Fish Hatchery. Follow the gravel road north about 7 miles to where it drops into a small valley; the bluffs and distinctive Morrison Formation can be viewed west and east of the road (private ownership, stay on road).

|

| The Morrison Formation exposed on the inner face of the hogback at Como Bluff. Looking westerly. Photo by Tom Rhea. |

More information about Como Bluff and the Fossil Cabin can found at these websites:

This is my contribution to Accretionary Wedge #42.

Sources

American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Online Collections (used with permission).

Breithaupt, B.H. ca. 1993. Como Bluff : the dinosaur graveyard. Laramie, WY: Geological Museum, Dept. of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming.

Breithaupt, B.H. 1991. Stop #1 - Como Bluff. in Sundell, Kent A., and Thomas C. Anderson. Road log volume for Rediscover the Rockies: AAPG-SEPM-EMD Rocky Mountain Section meeting, 1992. Casper, WY: Wyoming Geological Association.

Dunbar, R. O. 1942. The geology of Como Bluff anticline, Albany-Carbon counties, Wyoming. Thesis (M.A.)--University of Wyoming.

Mears, B., Jr., Eckerle, W.P., Gilmer, D.R., Gubbels, T.L. Huckleberry, G.A., Marriott, H.J., Schmidt, K.J., and Yose, L.A. 1986. A geologic tour of Wyoming from Laramie to Lander, Jackson and Rock Springs. Public Information Circular No. 27. Laramie, WY: Wyoming Geologic Survey.

About the Bone Wars:

Schuchert, C., and LeVene, C.M. 1940. O.C.Marsh, Pioneer in Paleontology. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Shur, E. 1974. The Fossil Feud. Exposition Press, NY.

Ostrom, J,H., and McIntosh, J.S. 1966. Marsh's Dinosaurs: The Collections from Como Bluff. Yale University Press, New Haven.

in many places fossils are crushed to make cement,so its good to see an entire cabin made of unbroken fossils! good history lesson too..thanks!

ReplyDeletethanks! I'm glad you enjoyed it, it was fun to put together

ReplyDelete