Lamoille Canyon, in the Ruby Mountains of northeast Nevada, is a geotripper's dream. Attractions range from Pleistocene sculptures to seriously-deformed mid-crustal Proterozoic rocks, all visible from the paved road up the canyon. And there are guidebooks! That wasn't always the case, of course. The first geotrippers had to decipher the geology themselves. They got some things right, but for others, they were wide of the mark.

In 1868, geologists Clarence King, Arnold Hague, and SF Emmons were traversing Nevada from west to east, during the second season of King's Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel. In August they reached the East Humboldt Range, which at that time included the Rubies. The men were impressed. They found it to be "the most prominent uplift lying between the Sierra Nevada of California ... and the Wahsatch of Utah" (Hague & Emmons 1877).

King's seven-year survey would result in five geologic maps and an epic report—eight volumes in all and nicely illustrated, with photographs even!

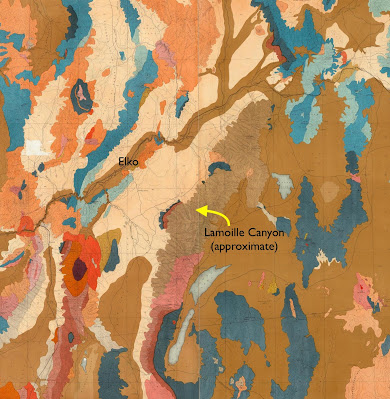

|

| From King's geologic map of the Nevada Plateau. Brown unit that includes Lamoille Canyon is "Archean"—everything older than Cambrian (David Rumsey Map Collection). |

|

| Lake Marian; chromolithograph by expedition artist Gilbert Munger (King 1878). |

Arnold Hague described the East Humboldt Range as a "bold" ridge 80 miles in length "with many rugged summits reaching over 10,000 feet above sea-level". Unlike most ranges in Nevada, it had been extensively glaciated. "The summits of the East Humboldt Range, from White Cloud Peak to the northern end, all show abundant evidences of glaciation. Very considerable glaciers existed in the elevated group south of Fort Halleck" [location of Lamoille Canyon]. "The erosion of glaciers has excavated deep U-shaped cañons ..."

|

| "Glacier Cañon" by Timothy O'Sullivan, expedition photographer (Hague & Emmons 1877). |

|

| Tarn above a U-shaped canyon—textbook glacial features (Hague & Emmons 1877; O'Sullivan photo). |

A valley's shape often indicates its creator. V-shaped drainages usually are the work of streams. Flowing water erodes the outsides of bends, and deposits sediment on the insides, making a narrow winding drainage. But a glacier can destroy those bends. Born at high elevations when enough snow and ice have accumulated, it oozes downstream, carrying and shoving rocks and debris—a giant icy rasp grinding away at anything in its path. Slowly it make the valley straighter, the bottom wider, the sides steeper—a U-shaped glacial canyon (more here).

|

| Lamoille Canyon is both V- and U-shaped; shorter U-shaped drainage is the South Fork, a hanging valley (modified from source). |

|

| V-shaped part of Lamoille Canyon. Pullouts are scarce. |

|

| Upper Lamoille Canyon is U-shaped, with nice pullouts for geo-gawking. |

The road continues upstream below walls of spectacularly-deformed rocks to a popular trail head. However the season was winding down. Though it was a weekend, my field assistant and I had the trail to Lamoille Lake to ourselves.

|

| From the start to the top, the trail provided great views of glacial sculpting. |

|

| Pegmatite vein intruded into granite, and polished millions of year later by ice. |

|

| Lamoille Lake in its cirque, viewed from about 10,300 ft (source; I didn't get this high!) |

|

| What the heck happened here?! |

As geologists learned more about the mountains of the American West—and more about geology itself—the Ruby and East Humboldt ranges revealed themselves to be a great puzzle. What's with the mid-crustal metamorphic rocks exposed at the surface, and those greatly displaced fractured sedimentary strata?! Not until the 1980s did someone come up with plausible explanation. It's a complicated story, and still debated. In an upcoming post I will attempt to describe metamorphic core complexes ... while the ghost of Clarence King sighs with relief that he lived in a simpler time.

|

| Geologists back in the day (1864); Clarence King far right (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution). |

Sources

DeCourten, F, and Biggar, N. 2017. Roadside Geology of Nevada. Mountain Press.

Hague, A, and Emmons, SF. 1877. Descriptive geology. Report of the geological exploration of the fortieth parallel, v. II. GPO.

King, C. 1878. Systematic geology. Report of the geological exploration of the fortieth parallel, v. I. GPO.

Snoke, AW, et al. 1997. Grand tour of the Ruby-East Humboldt metamorphic core complex, northeastern Nevada. U. Dayton, Geology Faculty Publications 39. Available here.

The diagram showing the Vs and the Us was helpful. Thanks for the inspiration. I need to spend more time in that part of the West. When we retire, we plan to travel in February...this would be an interesting destination.

ReplyDeleteRetirement and travel sound great, good for you!

DeleteA very favorite range. I describe it as the "BC Coast Range with all the glaciers gone".

ReplyDeleteInteresting! I liked it very much, and plan to go back this year for more exploring (not during hunting season this time).

Delete