|

Early-morning drink from a waterpocket in the Navajo erg.

|

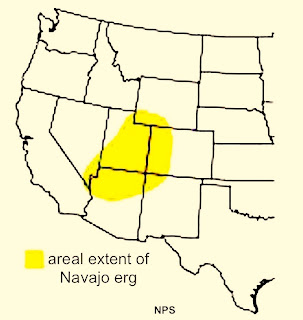

An erg is a “sand sea”, a large expanse of wind-deposited dunes or sheets of sand, like the Sahara of northern Africa and the Great Sandy Desert of Australia. Sand covered much of western North America ca 180 million years ago in what has been called the largest erg in the history of the continent ... or perhaps the largest anywhere, ever (Fillmore 2011). Today we call it the Navajo sandstone.

|

The sun sets on a “petrified dune” -- a remnant of the Navajo erg near Boulder, Utah.

|

The Navajo erg was in existence for some 15 million years during the early Jurassic, when North America was much closer to the equator, overlapping the zone of dry trade winds. Sand accumulation was massive in places, reaching thicknesses greater than 2500 ft ... for example at Zion National Park in southern Utah.

|

Navajo sandstone walls viewed from the East Rim Trail, courtesy Zion NP.

|

|

Large-scale cross-bedding attests to eolian (wind) origins. Navajo sandstone in the San Rafael Swell in central Utah; width of view is roughly 30 feet.

|

Fifteen million years -- the lifespan of the Navajo erg -- may seem like forever, but at the scale of geologic time it was just a moment. The erg was inundated by invading seas, buried in marine deposits and then under more sand when the seas retreated ... and so on, for the next 100 million years or so. Sand became sandstone under thousands of feet of overlying sediment.

Subsequent uplift, faulting, intrusion, weathering and erosion have exposed the Navajo, often quite spectacularly. I think these must have been terrifying landscapes for early travelers and settlers. But times change. Now many many many thousands of travelers come to the Colorado Plateau specifically to see this starkly beautiful scenery.

|

Navajo sandstone forms the outer wall of the San Rafael Reef in central Utah.

Photo by Jack Share; used with permission. |

|

Navajo sandstone “capitols” in Capitol Reef National Park form the backdrop for a Fremont cottonwood.

|

The Navajo sandstone frequently is pale in color and easy to distinguish from the common red rocks of the Colorado Plateau. Early geologists made note of this. John Wesley Powell called it the “White Cliffs sandstone” and G.K. Gilbert referred to it as the “Gray Cliffs group” (Longwell et al. 1932).

|

| Navajo sandstone domes and "mosques"; from Longwell et al. 1932, Plate IX in part. |

But the Navajo wasn’t always so pale. It probably was red sand originally, and then red sandstone for a while after burial. The red of red sandstone comes from very thin coatings of rusted or oxidized iron (

hematite) on individual grains. Some outcrops of Navajo sandstone remain red to this day, the films of

hematitic sand pigment still in place.

What happened to the rest? The Navajo, made up as it is of uniform wind-deposited quartz grains, is quite porous. When water of the right chemistry (reducing) moved through, iron went into solution and the rock lost its red color. In other words, the originally-red sandstone was bleached (e.g. Chan and Parry 2002).

|

| Some outcrops of Navajo sandstone remain red to this day, the thin films of hematic sand pigment still in place. This one is near Moab, Utah. |

|

Red strata and pockets can occur in otherwise-pale outcrops. These may be original unbleached remnants, or areas of re-oxidized iron. Photo by Jack Share; used with permission.

|

|

Rusty water streaks on the Navajo near Boulder, Utah.

|

Bleaching is just one example of the role of water in the history of the Navajo. This erg, like many, was not just dry sand. Large volumes of water moved through it, both while it was sand and after it became rock, and even today the Navajo sandstone is considered one of the best reservoirs and aquifers on the Colorado Plateau (Chan and Parry 2002). Water in the Navajo has created many intriguing features, in addition to variation in color.

|

| This Navajo outcrop along the highway in Capitol Reef National Park exhibits soft sediment deformation, perhaps of buried water-saturated sand. |

If iron-rich water passing through sandstone encounters oxygenated water, iron can precipitate out, again coating the sand grains. However, this is not just a thin film but rather a strong thick hematitic cement. If exposed, the chunks of cemented sandstone eventually weather out of the softer surrounding rock ... which takes us to the mysterious dark rocks in my kitchen, the subject of a

recent post.

|

| Still life with iron concretion -- aka iron oxide concretion, iron sandstone, ironstone. |

Iron concretions seem to be most common in areas where the Navajo has been bleached, suggesting they contain iron that once colored the sandstone red.

Moki marbles are the most famous,

but concretions come in many other shapes as well.

|

| Puzzling round iron concretions, called moki marbles; small block at top is 1 cm across. |

|

| Moki marbles in situ. Photo by Jack Share; used with permission. |

|

| Iron concretions from Navajo sandstone; width of view is 15 inches. |

|

| Navajo flatirons on the south side of Mt. Hillers in the Henry Mountains of southern Utah. |

The Navajo sandstone is spectacular in landscape view -- there's no doubt about that. But sometimes I find its close-up patterns even more fascinating, especially when I know something of the history they record.

|

| Ancient cross-bedding, from 180-million-year-old sand dunes. |

|

| Modern-day dog for scale. |

Navajo iron art in early morning light; all views from above, widths 6-15 inches:

|

| Iron concretion with moss. |

|

| Navajo sand on the move again, this time carried by water rather than wind. |

Sources (in addition to links in post)

Fillmore, Robert. 2011. Geological evolution of the Colorado Plateau of eastern Utah and western Colorado. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Brava! So well done! I love the way you depict your subject matter from such a unique perspective. Your photo-diversity is a wonderful compliment to your subject matter. I love the Navajo too, and yet there were so many (lesser) ergs as well. I believe in the Glen Canyon area you can count six distinct sandstone strata.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Jack, for the kind comments. Sand makes such wonderful landscapes, whether loose or lithified ... I'm glad there was so much out there for so long :)

Delete