|

| Equisetum hyemale is an able colonizer in spite of its lazy sporangia. Nevada roadcut, Matt Lavin photo. |

|

| Equisetum's simple beauty. Unbranched species are often called scouring rushes. Andre Zharkikh photo. |

Though horsetails are technically ferns, their leaves differ radically from those of true ferns. In fact, at first glance it appears there are no leaves. But there are—just highly modified. Whorls of leaves occur at each node (not to be confused with branches in branched species). They are fused into a sheath that looks very much like the stem. The tips remain separate, forming a ring of "teeth" at the top of the sheath (deciduous in some species).

|

| Tan sheaths are fused leaves, topped with a ring of black leaf tips (teeth). Matt Lavin photo. |

|

| Field horsetail, E. arvense, is a branched species. In the absence of green leaves, photosynthesis occurs in the stems and branches. Andre Zharkikh photo. |

|

| In Equisetum, spore-producing sporangia reside in cones at tips of fertile stems. In field horsetail, fertile stems are flesh-colored. Green branched sterile stems emerge later. |

|

| Uncurling elaters of a horsetail spore. Source. |

Then Marmottant and colleagues (2013) followed horsetail spores with a high-speed camera. They discovered that elaters function not as wings but as legs. Elaters allow spores to walk, and even better, to jump high enough to catch the wind!

Spores "walk" by extending their elaters with drying, and then shifting a little when humidity increases and the elaters curl back up. This is more like a random meander than a walk (image below), but it can get a spore out of tight situation, like being stuck to something.

If for some reason elaters can't gradually uncurl as they dry, elastic energy builds up until the stress is too great. Then suddenly the elaters uncurl, launching the spore. It may jump a full centimeter off the ground! This is a large distance compared to its size, and enough to catch a ride on windy days.

Spores can hop repeatedly because hopping doesn't damage the elaters. The authors of the study speculated that because jumps occur with drying, they are a way to escape from dry locations, hopefully to places with more moisture. The authors also "believe that this study will inspire new biomimetic classes of self-propelled objects ... ". Will groceries one day hop to our doorstep?

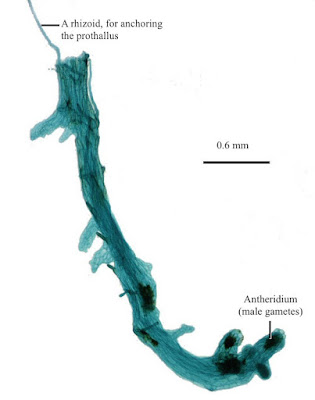

The image above shows a field horsetail spore in action. Top left—elaters partly uncurled with drying. Bottom left—path of spore "walking" in response to repeated changes in humidity; average step is 31 µm. Right—hopping horsetail spore in its first 3 milliseconds of travel after taking off at a speed of 0.35 m/sec. Modified from Marmottant et al. 2013.If a spore lands in a suitable spot, it will germinate not into a horsetail like its parent, but a prothallus, the gametophyte or sexual plant that is part of the life cycle of all ferns. For a simplified version of the full story, see my previous post "Fern Seeds?"

|

| Equisetum gametophyte; those of true ferns are typically heart-shaped or bilobed. Source. |

Sources

Llorens, C, et al. 2015. The fern cavitation catapult: mechanism and design principles. J. R. Soc. Interface 13: 20150930. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2015.0930

Marmottant P, Ponomarenko A, Bienaime ́ D. 2013 The walk and jump of Equisetum spores. Proc R Soc B 280: 20131465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.1465

Moran, Robbin. 2004. A Horsetail's Tale? in A Natural History of Ferns. Timber Press.

I've always found them fascinating. When I was a kid growing up in central Wisconsin, we lived across the street from a channel lined with trees and plants. There were so many horsetails! We would pull them apart and put them back together and make jewelry and other items with them. Thanks for all the information about them!

ReplyDeleteNice, I really like fun childhood memories :)

DeleteVery interesting, I've always been intrigued by horsetails. There's a nice patch in one of our local cemeteries.

ReplyDelete