Laramie residents know the power of wind. It drives turbines, knocks over semi-trucks, builds huge snowdrifts that close highways, and sends hoards of tumbleweeds racing into town. Spring breezes reach 35 mph, with gusts to 65 or more. Yet the wind was even worse during the last Ice Age. That’s when it excavated the Big Hollow, the largest deflation hollow in North America and a classic example of topographic reversal.

|

|

The Big Hollow is a product of deflation—excavation by wind. Even more astonishing, it was once a hill and its rim was a drainage bottom! Details to follow.

|

|

|

The green and white roughly-circular features within the blue oval are small deflation hollows occupied by internally-drained saline lakes and playas (modified Google Earth photo).

|

Huge as it is, the Big Hollow is easy to miss. While a mountain range stands above its surroundings, where it can be readily admired, a hollow lies below and is easily overlooked. But it doesn’t have to be that way. West of Laramie, US Highway 130 traverses the north rim. Look south from the road to grasp the immensity of the Big Hollow (even at 70 mph).

|

| View across Big Hollow from the north rim; arrow points to the south rim. |

How did wind blow away so much land? And why here specifically? To understand, let's visit the rim of Big Hollow 200,000 years ago. Bring an extra-warm coat and a snug-fitting hat!

|

|

Medicine Bow Mountains and adjacent Laramie Basin during the last Ice Age; by Samuel H. “Doc” Knight, Mr. Geology of Wyoming and master of block diagrams (modified from Knight 1990).

|

It’s the height of the Ice Age, and even though we’re 500 miles south of the continental ice sheet, the impact is obvious. The Medicine Bow Mountains to the west are buried under a thick layer of ice and snow, with only the high Snowy Range visible. Glaciers extend down drainages, and frigid meltwater streams rush out into the basin. There they slow and drop their loads of eroded debris, spreading gravel and rocks across the land.

The Laramie Basin is a scene straight out of the arctic. It’s covered in permafrost, a thick layer of soil frozen year round. The immediate surface thaws during warmer months, but the season is too short and dry for much to grow. Into this harsh barren world, a cold west wind roars down from the Medicine Bow Mountains.

The biggest surprise is the immediate landscape—it’s turned on its head! We’re standing not on a rim but in a drainage bottom, on a floodplain covered in rocks and gravel carried down from the mountains. And look south. Instead of a giant hollow, there’s a hill!

|

|

Big Hollow in early to mid Pleistocene time.

|

As we travel the 200,000 years back to the present, we will carefully watch the wind dig the Hollow so that we can understand how the landscape was changed so dramatically.

Several things are needed for a deflation hollow in addition to wind. There must be material light enough to be blown away. The Laramie Basin meets this requirement. The bedrock is soft shale that can be churned up by freeze-thaw, and crumbled into dust and dirt. With so little vegetation, the loose material readily blows away.

But a hole is more than empty space. It needs a rim and sides to define it. In the case of the Big Hollow, the rim consists of a layer of rocks and gravel left by a former tributary of the Laramie River. They’re too heavy for wind to carry off, and form a wind-resistant cap that protects the underlying shale from erosion.

|

Gravel and rocks on the rim are often cemented with caliche—a naturally-occurring cement (calcium carbonate).

|

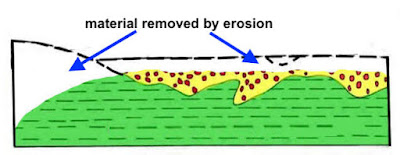

As we time-travel back to the present, we watch the wind erode and lower the shale surface bit by bit, year after year, while the erosion-resistant gravel-capped surface stays relatively high. Geologists call this topographic reversal. A high point on the landscape becomes low, and the old lowland is left standing high. The Big Hollow is a National Natural Landmark in part because it’s a classic example of topographic reversal.

Here's topographic reversal in action (modified from Mears 1987):

First, a former tributary of the Laramie River spreads gravel and rocks from the Medicine Bow Mountains across the floodplain, next to a hill made of shale.

Next the stream shifts course, abandoning the channel. Wind erodes the shale faster than the gravel and rocks.

Today the old drainage bottom is a high point (rim), and the hill has become the Big Hollow. “The hollow represents a classic case of ‘topographic reversal …’” (National Park Service).

Tour the Big Hollow

This tour starts in Laramie and makes a clockwise loop around the Big Hollow via US Highway 230, the Big Hollow Road (well-maintained gravel), and US Highway 130. It can be done in winter but check road conditions first. Most of the land is privately-owned, limiting us to views from roads; exceptions include several public lakes (turnoffs signed).

From the junction of US Highways 130 and 230 in Laramie, take 230 west eight miles and turn right on Pahlow Lane. After about five miles, turn right on Big Hollow Road, County Road 44. Shortly pass Twin Buttes Reservoir on the left; now pay close attention. After about 1.5 miles, the road starts to climb the south rim of the Hollow. It's not as prominent as the north rim and easy to overlook. Leave the south rim at the warning sign (40 mph) and drop into the Hollow. Note the north rim beyond (geo-geek photo op!).

Cross the narrow west end of the Hollow, passing the Big Hollow anticline (fold) on the right, marked by a small oil field. The road then winds up to the north rim. Near the top, stop to study small road cuts exposing the rocks and gravel that cap the rim.

At the junction with US Highway 130, pull off on the right side of the Big Hollow Road. Take advantage of this opportunity as pullouts are scarce along 130. Saunter back down the gravel road to admire the Big Hollow.

Turn right (east) onto 130, toward Laramie. Read your odometer or set it to zero. For the first mile, the highway runs close to the rim with good views of the Hollow, but unfortunately there are no pullouts. At 3.5 miles, you might want to stop at the Overland Trail historical marker—a sizable pullout but on the wrong side of the road.

About six miles from the Big Hollow Road, pay close attention. At 6.3 miles, take an unmarked turnoff right (this is across the highway from green mile marker 7). Note the unlocked gate and sign. This is State land, accessible to the public. Go through (and close) the gate, and park on the rim. Be careful getting off and on US 130. It can be busy, especially on weekends, and the speed limit is 70 mph.

|

| The gate is easy to operate. |

Here on the rim, the ground is littered with gravel and rocks from the Medicine Bow Mountains, carried down by that former tributary of the Laramie River. After strolling along the ancient stream, you can walk south down into the Hollow not quite a mile before reaching private land.

Back on the highway, continue east (right) toward Laramie, passing the east end of Big Hollow just before the airport. A few more miles takes you into town and back to the junction with US 230.

|

|

View west across Big Hollow. The old stream channels that form today's rims joined near the airport (large X). Red arrows approximate tour route. Modified from Mears 1987.

|

Sources

Blackwelder, E. 1909. Cenozoic history of the Laramie region, Wyoming. J. Geol. 17(5): 429-444.

Hausel, W.D., and Jones, R.W. 1984. Self-guided tour to the geology of a portion of southeastern Wyoming. Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular 21, 44 p., 1 pl., scale 1:500,000.

Knight, SH. 1990. Illustrated geologic history of the Medicine Bow Mountains and adjacent areas, Wyoming. WSGS Memoir No. 4.

Mears, B, Jr. 1987. Late Pleistocene periglacial wedge sites in Wyoming: an illustrated compendium. Geological Survey of Wyoming Memoir No. 3. [see Introduction for information about Big Hollow.]

Mears, B, Jr. 1991. Laramie Basin, p. 418-427 in Rehis, M.C., Palmquist, R.C., Agard, S.S., Jaworoski, C., Mears, B., Jr., Madole, R.F., Nelson, A.Rr, and Osborn, G.D.1991. Quaternary history of some southern and central Rocky Mountain basins, Ch. 14 in Morrison, R.E., ed. Quaternary nonglacial geology: conterminous U.S., in GSA, The Geology of North America Volume K-2.