|

| Tweedy's Pussypaws, Lewisiopsis tweedyi, is one of at least 35 species named for topographer and botanist Frank Tweedy. Thayne Tuason photo. |

Frank Tweedy was an assistant topographer with the Northern Transcontinental Survey, which was in the process of establishing a railroad route to the coast. The boss, R.U. Goode, had hoped to set up a survey station on a peak near Snoqualmie Pass, but Tweedy carried the theodolite (for measuring angles). Because of his botanical dawdling, the day ended in failure.

"You jolly well made an ass of yourself!" Tweedy fumed, while waiting for the others to return to camp. But to his surprise, he wasn't fired. Instead Goode calmly explained, "You can't make a success of two things, botany and topography both, at the same time." But Goode was wrong.

|

| Frank Tweedy, date unknown. Union College archives, used with permission. |

New England Beginnings

Frank Tweedy was born in New York City in 1854. After graduating from Union College (Schenectady) with a degree in civil engineering, he spent four field seasons surveying and mapping for the Adirondack Survey. He also collected plants.

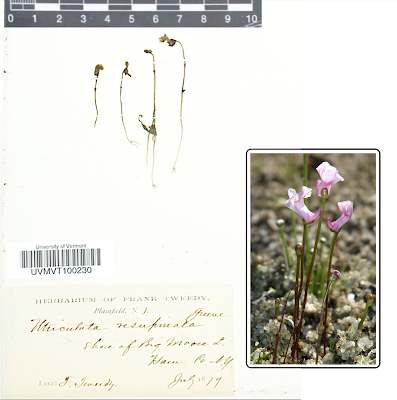

Tweedy's botanical training remains a mystery, but his specimens show he was a serious and able botanist (1). He didn't shy away from difficult groups, and apparently found wetland plants especially interesting, collecting bulrushes, pondweeds, bladderworts, and numerous sedges. He published his discoveries—state records and notable range extensions—in the Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club.

|

| Tweedy specimen (in part) of Northeastern Bladderwort, Utricularia resupinata. "I do not think it uncommon through northern New York," he reported in 1880. US National Herbarium, scale in cm; added color photo by Doug McGrady (CC BY 2.0). |

To the American West, Land of Discovery

Tweedy's botanizing underwent a radical change in 1882, when he was hired by the Northern Transcontinental Survey and sent to Washington Territory. No longer need he concern himself with range extensions. This was a botanical frontier, largely unexplored. A sharp-eyed collector might well find "novelties"—species new to science!

|

| Tweedy's Reedgrass, from American Grasses by Frank Lamson-Scribner, 1897. |

|

| Tweedy's Plantain. Andrey Zharkikh photo. |

Tweedy worked for the USGS in the Rocky Mountains for two decades, collecting plants wherever he went. Among his more productive projects were the Livingstone and Dillon topographic maps in southwest Montana, where he nabbed at least ten new species, including Tweedy's Daisy, Snowlover, and Thistle (Erigeron tweedyi, Chionophila tweedyi, and Cirsium tweedyi [now part of C. eatonii]).

|

| Chionophila tweedyi, Tweedy's Snowlover. Matt Lavin photo. |

Names Come and Names Go

As budding botanists, we're taught to use scientific names in spite of the off-putting Latin. We're told they are unambiguous, universal, and enduring. But then when we go out into the real world, we learn otherwise. Scientific names do change, and more frequently than some of us would like!

There are many reasons for name changes, but one is especially common—the "law of priority" (Mori 2013). If a given species is described and named by more than one botanist, the first-published name is accepted (others become synonyms). The law of priority was frequently broken in the 19th-century American West, understandably. Floras and relevant literature were inaccessible or non-existent, and communication with other botanists was slow at best.

In the case of Frank Tweedy's discoveries, an additional factor was at play. Like many plant collectors then, he sent specimens of interest to experts at botanical institutions. They decided which were new species, and then described and named them.

|

| Per Axel Rydberg, author of Flora of the Rocky Mountains and adjacent plains (1917). |

In 1901, Tweedy was surveying the Encampment mining district, which was mostly in southern Wyoming. However, "By reason of the faulty determination of the forty first parallel ... the State boundary was located approximately one third of a mile north of its proper position [and] consequently a narrow strip along the southern edge of the district ... is in the State of Colorado" (Spencer 1904). It was in this sliver of Colorado that Tweedy collected an interesting beardtongue. He sent the specimen to Rydberg, who designated it the holotype (basis for description) for a new species, Penstemon cyathophorus.

|

| Tweedy's 1901 North Park Beardtongue specimen (US National Herbarium). Click to view 4 exserted stamens circled in the added closeup . |

End of an Era

Why did Tweedy find only one true novelty in Colorado? The answer probably is timing. Though the Rockies would continue to yield new plant species, the great era of botanical exploration was coming to a close by the early 1900s. No longer could a sharp-eyed plant collector rake in novelties (Williams 2003).

Did Tweedy realize what was happening? Is that why his large-scale botanizing ended after his Colorado projects? We don't know. In any case, after a field season in New Mexico, he worked for the USGS in Washington DC until his retirement in 1926. He lived another decade before passing away in 1937 at age 83 (Lesica & Kruckeberg 2017).

In his day, Frank Tweedy was highly respected as a pioneering botanist in the American West, with at least 35 species named in his honor. So it's surprising how few of today's botanists have heard of him. And until a few years ago, his presence online was negligible. But that has changed. Now there's a Wikipedia article where you can learn more about Tweedy's successful endeavors "in both botany and topography, at the same time." (2)

|

| P.A. Rydberg named Ivesia tweedyi for Frank Tweedy, who made the first collection in 1883, in Washington Territory. Photo by brewbooks. |

Notes

(1) The SEINet Portal Network is the source of information here about Tweedy specimens, unless noted otherwise. Digitization of herbaria is a work in progress; counts likely will change.

(2) Despite his early reprimand, R.U. Goode likely approved of Tweedy's double successes, for he became a close friend, and served as best man at Tweedy's wedding.

Sources (in addition to links in text)

Lesica, P and Kruckeberg, A. 2017. Frank Tweedy (1854–1937) in Potter, R, and Lesica, P (eds.). Montana's Pioneer Botanists: exploring the mountains and prairies. Montana Native Plant Society.

Spencer, AC. 1904. Copper deposits of the Encampment District, Wyoming. USGS Prof. Paper 25.

Tiehm, A, and Stafleu, FA. 1990. Per Axel Rydberg: a biography, bibliography, and list of his taxa. NY Bot. Gar. Mem. 58 (75 pp).

Tweedy, F. 1926. The Confessions of a Tenderfoot. Unpublished memoir.

Williams, RL. 2003. A Region of Astonishing Beauty—the botanical exploration of the Rocky Mountains. Roberts Rinehart Publishers.