|

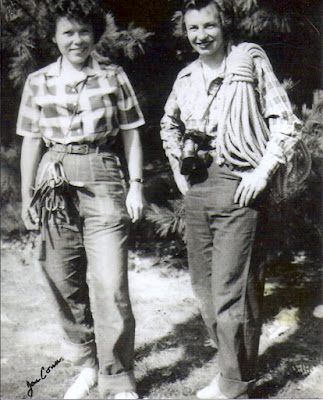

| Jan Conn (center) with her woodworking group. |

Jan Conn passed away in May at age 99. She was a valuable part of my life, following a lifestyle to which I aspired, encouraging me in music, sharing my interest in native plants, and showing by example that being one's self, enjoying life, and helping others do the same are so important. Maybe this short account of Jan and our friendship will encourage others as well.

|

| It was while I was working as a ranger at Devils Tower that I first learned of the Conns. |

In 1948, Jan and her husband Herb drove to northeast Wyoming in their converted panel truck and climbed Devils Tower, an 800+ ft rock monolith rising from the valley of the Belle Fourche River. Jan thereby nabbed the first female ascent (not counting Linnie Rogers who used a

wooden ladder). Four years later, Jan repeated the climb with Jane Showacre, making the first manless ascent!

Devils Tower was just one stop of many in their wanderings. The Conns drove from area to area, living in their little camper, climbing, working the odd job, climbing, working, climbing ... actually mostly climbing. Really?? I totally understand the lifestyle, I know it well. But these people are old enough to be my parents! Yet that was indeed what they did, living the dream, doing first ascents and establishing new routes from the east coast to the west. The Conns have been called the first climbing bums. And after the great

Fred Beckey passed away in 2017, Jan was anointed

the oldest living dirtbag.

|

| Jan and Herb in their converted panel truck, 1957 (source). |

|

| Camping at Devils Tower, 1956 (source). |

In the early 1950s the Conns settled near Custer, South Dakota, in the high country of the Black Hills. The area was filled with granite spires, fins and massifs awaiting first ascents, which they happily supplied. Then in 1959, a friend introduced them to caving by way of a "small" local cave (Jewel Cave) and they were hooked. Supporting themselves by selling leatherwork, giving music lessons, and living really cheaply in the Conncave, they would discover and map 62+ miles!

By the early 1980s, they had "retired" from caving and returned to climbing. That's what they were doing when I had the good fortune to share a bit of their lives.

One day Jan invited me to an ascent of the 3BT massif (a classic Conn name meaning 3 Billion Tons). Should I, of intermediate skill, join two world-renown climbers? Sure, why not?! After all, these were white-haired elf-like characters in their early 80s.

We followed a secret winding trail marked by subtly arranged pine branches to the base of the massif and into a deep rock-walled gully, which soon narrowed. Here I observed a conn-flict, a rare event. "Herbie, I think we go this way." Herb smiled, "No, we go up the gully a bit further." Jan wasn't conn-vinced, "But I remember that tree." "We need to head for that chockstone" Herb said, pointing up the gully. This conn-tinued for another minute or so until I interjected dramatically, "Quit fighting!!" We all burst out laughing.

Herb was right of course (he was the mapper in the family), and so we scrambled up the gully, wriggled around beneath the chockstone, roped up for a short section of easy climbing, and then strolled to the summit.

|

| Getting close to the top! |

|

| Headed home after a successful ascent of 3BT. |

Climbing was not the only kind of adventure Jan offered. One day, having learned I played recorder, she asked if I would come to the monthly Hootenanny (Jan was a product of the Beat Era). It sounded like fun until I learned that all attendees had to perform. She suggested we perform a duet for flute and recorder.

Oh dear. I was untrained and played only for my own enjoyment. Yet like all things Conn, it turned out to be fun. Performances ranged from a boy's poem about his frog (in his hand) to a phone company employee demonstrating how to hook up a new phone line. We fit right in. I would go on to play and perform with the French Creek Folk (Jan and any locals that were available) until I left the Black Hills.

|

| French Creek Folk c. 20 years ago. Jan on bass next to Hollis on fiddle. |

|

| Jan was (in)famous for her yodeling, including underwater (watch here). |

And there was more. Jan told me about an odd fern they had found on one of their climbs. Since I was a botanist, she was sure I would know it. The three of us went to investigate, with a rope. Herb led the climb, Jan and I followed. There they were—two different ferns, one of which I did NOT recognize. After consulting with an expert who confirmed that it was a significant range extension, we published our discovery in the

American Fern Journal!

|

| Botanizing by rope; Jan pointing to fern habitat. |

Having shared some of my stories, I will finish with links to others. The Conns were special to many people in many ways. The final sentence of the first article below says it all: "It has been a wonderfully satisfying life for the Conns, just doing what appealed to them, and they are grateful if their fun has brought things of value to others." Indeed it has!!

|

| Herb and Jan at home in the Black Hills. |