|

|

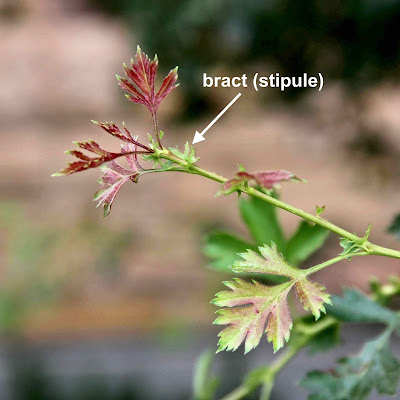

Cars on Libby Flats at the base of the Snowy Range, southeast Wyoming; July 4, 1926; courtesy American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

|

This article will appear in Sunday's Laramie Boomerang, our daily newspaper, founded in 1881 by Bill Nye. He named it after his mule “who always came back.” I contribute to the popular “Laramie’s Living History” column, usually writing about botanical and geological features. But this is all human history, with the exception of some “glacial ice.”

Celebrating the “Great Skyroad”

On the morning of July 4, 1926, it was raining hard. But that didn’t stop the watermelon crew. They left Laramie early, reaching the summit well in advance of the ceremonies. There they buried two tons of melons in snow. Unfortunately, by mid-day the new road was thoroughly soaked, and struggling automobiles had churned it into an unnerving muddy mess. Many turned back. The Governor arrived two hours late.

Yet the ceremony went largely as planned, with hundreds of chilled but cheerful onlookers celebrating the opening of the Great Skyroad across the Snowy Range. Though the name didn’t stick, the road was a great success, opening areas previously inaccessible, and allowing for many activities across the range.

FIFTY YEARS OF IMPROVEMENTS

The first wagon roads into the high Medicine Bow Mountains appeared in the 1870s, built by loggers, miners, and tie hacks from the railroad. By the late 1890s a road of sorts extended across the range. But sections were quite rough, barely passable to wagons.

In 1909, the Forest Service, Albany County, and the town of Centennial contributed a total of $2500 for road improvements between Centennial and Brooklyn Lake. The first auto arrived at the lake a year later, a new Franklin driven by Forest Supervisor P.S. Lovejoy. The nine-mile trip (one-way) took an hour. Lovejoy must have been an adventurer and skilled driver, for the road to the lake was said to be impassable to autos, and would remain so for a decade.

[NOTE: This Lovejoy is not to be confused with Laramie’s inventor Elmer Lovejoy, of bicycle and automobile fame, and it’s unknown whether the two were even related. But Supervisor Lovejoy may well have bought the Franklin he drove to Brooklyn Lake at Lovejoy Novelty Works, where Elmer sold both bicycles and automobiles. P.S. Lovejoy left Laramie around 1911, moving to Ann Arbor to teach in the Forestry program at the University of Michigan.]

|

|

Elmer Lovejoy’s Garage and Service Station c. 1920; courtesy Laramie Plains Museum.

|

In 1920, the federal Office of Public Roads and Rural Engineering (today’s Federal Highway Administration) provided Wyoming with $25,000 to improve the road to Brooklyn Lake, which had become popular with local recreationists and, increasingly, tourists. Those sections not covered by the feds were upgraded by Albany County.

The obvious next project began in 1924—a road passable to autos across the high Medicine Bow Mountains. Fully funded by the federal government, it would continue 22.5 miles west from the Brooklyn Lake road to the Forest boundary, where it would join with an existing road from Saratoga. The roadway would be ten feet wide with a surface of graded dirt (graveling and then paving of the Snowy Range Road didn’t start until the 1930s).

BIGGEST PICNIC EVER

By the summer of 1926, the road over the Medicine Bow Mountains was essentially in place. A dedication ceremony was in order, and what better day to celebrate than July 4, our nation’s birthday. A committee was formed, and plans were made. On July 3, the Laramie Republican-Boomerang announced that the dedication exercises, which would start at noon, would be followed by “the biggest picnic ever held in the state.” Watermelons chilled in “glacial ice” and hot coffee would be provided. Attendees were to bring their own lunches.

But first the road had to be cleared of snow on both sides of the summit—not surprising given the earliness of the season. A call for volunteers went out. The Wyoming Reporter, a Rawlins paper, assured readers that a crew of 30 had successfully cleared the route with picks and shovels, though in places autos would have to pass between snow banks 10 to 15 feet high. Saratoga and Centennial supplied most of the volunteers, along with a few from the University (including President A.G. Crane). Notably, even though a “large number of people from Laramie were in the Snowy Range region … few volunteered to help open the road.”

On July 1, special traffic regulations for the day of the celebration were announced in the Laramie Republican-Boomerang: “Forest and sheriff’s officers will be stationed at key points along the highway, and between the hours of 10 and 12, only ‘up’ traffic will be permitted. Between 12 and 2 will be reserved for ‘down’ traffic and the hour between 3 and 4, if necessary for ‘up’ traffic. A speed limit of fifteen miles per hour will be in effect on all sections of the road where the need warrants.” As it turned out, 15 mph was overly optimistic.

BRAVE DRIVERS REAP REWARDS

July 4 dawned rainy, with especially heavy downpours on the east side of the range. This “greatly hindered the progress of the multitude of automobiles that had come for the exercises” according to the Laramie Republican-Boomerang. The wheels of hundreds of cars soon made the road slick and dangerous. Many turned back, especially those from Laramie and Cheyenne, the road up the east side being particularly treacherous.

However state officials led by Governor Nellie Tayloe Ross, along with representatives of the Forest Service and dignitaries from Rawlins, Laramie, Cheyenne, Parco, Saratoga and Encampment, braved the conditions and reached the summit, though two hours late. But that was just as well, as the skies had cleared only an hour before.

There they found either 400-500 (Rawlins Republican) or 600-700 (Saratoga Sun) participants in a celebratory mood. A huge fire roared nearby, and, at the encouragement of President Crane, people were loudly singing “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No More …”

A speaker’s platform had been assembled from two table tops, laid across the sides of a truck. Here the most important dignitaries sat while Governor Ross dedicated the “Great Skyroad” (see photo). The Laramie Republican-Boomerang would report the following week that “Governor Ross made a particularly fine appearance that morning, standing up there on the roughly improvised platform, and her voice which is especially clear and pleasing, seemed to reach even the outer edges of the crowd, who paid their marked attention.”

|

|

Warmed by a roaring fire, Governor Nellie Tayloe Ross (standing on platform) dedicates the "Great Skyroad" over the Snowy Range; July 4, 1926; courtesy American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

|

According to the Boomerang, ceremonies were carried out as planned “with some necessary omissions.” Hundreds of chilled watermelons were enthusiastically consumed. However, the Rawlins Republican reported that participants from the west side of the range were “sadly disappointed” when the promised hot coffee was nowhere to be seen on Libby Flats. Instead, it was available 15 miles down the road toward Laramie, where lunch for the official party was being served. Given the slippery roads, a 30-mile side trip did not appeal to those returning home to the Platte Valley. “Why the coffee was not served at the point where the exercises were held is a mystery.”

The following week, local papers were in general agreement that the ceremonies and especially the new road were a great success. The Boomerang argued that given the morning’s storm, “it would not be fair to judge the road by its condition on Sunday … any road having something like half a thousand cars churning over it both coming and going is bound to manifest the effects.” Those who reached the summit and even those who made it just partway “were enthusiastic with what they saw, the wonderful vistas of mountains in the distance and the plains stretching beyond the almost countless lakes and ponds of beauty and the rushing, tumbling streams.”

The Saratoga Sun was equally effusive but more succinct: “In spite of the discomfort occasioned by the downpour of rain, however, all were agreed that the new highway has opened to public travel a wonderful scenic region, which will no doubt prove to be a favorite resort for outers and vacationists during this and succeeding summer seasons.” So true!

[by Hollis Marriott, Contributing History Columnist; Laramie Boomerang, August 18, 2019]

Sources

Wyoming Highway Department & Federal Highway Administration. 1988. Dedication ceremony; New Wyo 130 (Snowy Range Road). 12 pp.