As the authors state in their first sentence, Ecology of Dakota Landscapes was written "to share our enthusiasm for the natural history of North Dakota and South Dakota ..." But this also is a book about destruction and hope. The Dakotas exemplify the conflict between our love of nature and our survival needs—food in this case. Will we find a way to sustain both agriculture and our natural heritage? In their final sentence, the authors leave us wondering about the future: "The challenges are great, time seems short, the ongoing quest to make a sustainable living continues."

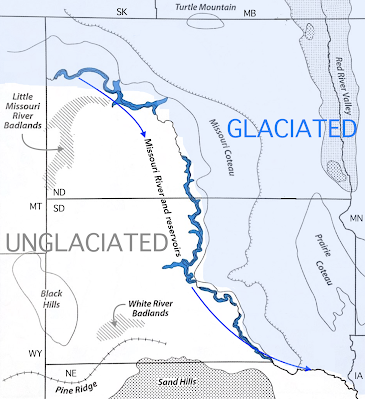

Dakota Landscapes begins with a three-chapter introduction to geography, ecosystems, geologic and human history, and climate (including a discussion of climate change). North and South Dakota are part of the Northern Great Plains, where summers are hot and often dry, and winters can be very cold. The Missouri River crosses the two states from northwest to southeast, separating areas with very different geologic histories. North and east of the river, glaciers repeatedly advanced from the north until just 10,000 years ago; landscapes are young, with flat to undulating terrain. In contrast, ice sheets rarely extended south and west of the river. Instead some sixty million years of deposition and erosion have created rolling plains dotted with buttes, badlands, and canyons. Far to the west, at the South Dakota/Wyoming state line, are the Black Hills—a striking outlier of the Rocky Mountains.

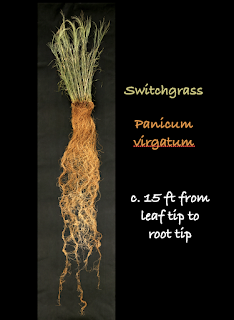

After the introductory chapters, the book is organized by ecosystems, both native and human-created. Grasslands, which occupy the greatest area (40%), come first. Evolution has made Dakota grasslands naturally resilient. Grasses will grow new leaves in response to grazing, and their rigid cell walls reduce wilting. The majority of grassland biomass—as much as 80%—lies below the surface, where "every cubic yard of soil has miles of plant roots and fungal filaments (hyphae) that sustain millions of bacteria and thousands of invertebrates". Death and decay underground are major contributors to soil fertility. The majority of prairie grasses are perennial and have shallow underground buds, allowing regeneration after surface disturbance.

|

| Photo by Dehaan, modified. From the Land Institute, used on many websites (source of height). |

The most extensive native grasslands in the Dakotas are the mixed-grass prairies of the drier west. They have long been grazed, originally by bison, now mostly by cattle. When properly-managed, grazing removes surface matter without damaging the ecosystem. In contrast, most of the tallgrass prairies of the wetter eastern Dakotas have been damaged beyond recovery, victims of conversion to cropland. This sad tale begins the next chapter, "Agriculture and Agroecology".

The glaciers that advanced across the eastern Dakotas created ideal farmland, and when settlers arrived in the late 19th century, they found millions of acres of rich soil. But it was covered in thick grasses as much as six feet tall. So before planting crops, they broke and removed the sod, including all the vital underground biomass. The consequences—soil erosion, sedimentation of streams and wetlands, and decline in water quality—contributed to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Though agricultural practices improved in response, the land never fully recovered. Now fertilizers, insecticides, and herbicides are needed where native grasses once thrived on their own.

Another gift of glaciation is the Prairie Pothole Region (PPR), which extends south from Canada through much the northern Great Plains, including the eastern Dakotas. When the ice sheets vanished, they left behind thick deposits of glacial debris containing huge chunks of ice. These melted to form tens of thousands of water-filled depressions—a system of lakes and wetlands known as the "nursery of North American Ducks" (or simply "the duck factory").

|

| Prairie Potholes, North Dakota. USFWS photo. |

The book's subtitle is Past, Present, and Future. That last word is the challenging subject of the final chapter, "Working toward Sustainability". Dare we hope to preserve native ecosystems and achieve sustainable agriculture? And in the face of climate change? The answer is ... maybe. Native ecosystems remain a large and important part of Dakota landscapes, and appreciation for them has grown. Agricultural practices have improved dramatically since the Dust Bowl; now there are encouraging examples of restorative agriculture and promising new methods to try. But change at the scale needed won't happen unless everyone contributes—that includes consumers (us!) as well as producers.

Ecology of Dakota Landscapes is both rigorous (e.g., sources are cited with endnotes) and readable. It will appeal to a wide audience, including outdoor enthusiasts, landowners, conservation biologists, policy makers, teachers, and students. The text is greatly enhanced by an exceptional collection of 200+ color photos and maps, with substantive captions.

Because of the immense range and amount of information, this is not a book to read once, cover to cover. And some readers may find the occasional science-dense sections off-putting, but these can be skipped with no harm done. Perhaps begin by perusing the many wonderful images and maps—it will be a solid introduction, and a fine way to plan your next Dakota outing.

|

| Sand Lake Wetland Management District on the Missouri Coteau, South Dakota. USFWS photo. |

|

| Deciduous forest surrounds a wetland on Turtle Mountain in far north North Dakota. Photo by Ken Lund. |

Notes

(1) To learn more about the book from the authors themselves, watch their recent book launch event on YouTube.

(2) The full citation is: Johnson, W. Carter, and Knight, Dennis H. 2022. Ecology of Dakota Landscapes; Past, Present, and Future. Yale University Press; Biodiversity Institute, U. Wyoming. ISBN 978-0-300-25381-8. Available in print and ebook format.

(3) Ecology of Dakota Landscapes was printed in China. It arrived in the US in March 2022 aboard the container ship Ever Forward, which went aground in Chesapeake Bay. It would take five weeks, two barges, and five tugboats to dislodge it, but only during a spring high tide and after removing 500 of the 5000 containers. Photo courtesy US Coastguard via Flickr (cropped).