|

| Petrophytum caespitosum mat on limestone. Dark spots are shadows cast by flower clusters. |

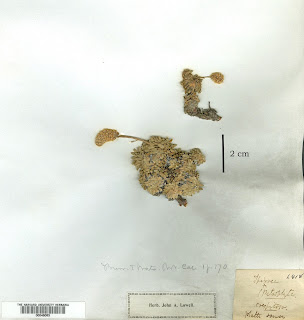

It was first collected by the great pioneering botanist Thomas Nuttall, probably in 1836, probably somewhere in the southeast quarter of Wyoming. His specimen—two small fragments, each with a flowering stalk—now resides at Harvard University (HUH; closeup below). Nuttall's yellowed handwritten label in the corner is terse: "Spiraea (Petrophyta. Caespitosa. Platte [River] sources." We shouldn't blame him. The expedition was on the move; time and space were limited. Large specimens and detailed location information were out of the question. Furthermore, it was an exploratory expedition. The country was still being figured out.

|

| Spiraea caespitosa collected by Thomas Nuttall. (HUH; lower right corner of herbarium sheet; scale line added). |

The next known collection was made by William Whitman Bailey, botanist with Clarence King's Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel. He found it in September of 1867, in the West Humboldt Mountains in western Nevada. His collection also resides at Harvard. But Bailey went further. That winter, he made a sketch of the rockmat eponymously sprawling across rock. It was added to the herbarium sheet, showing what can't be seen in a dried pressed specimen.

|

| WW Bailey's Spiraea caespitosa (one of six specimens, from various collectors, on a single sheet; HUH). |

|

| Bailey's sketch of Spiraea caespitosa in the West Humboldt Mountains (HUH). |

From San Francisco, Watson took the train as far east as it went, and then walked across the Sierra Nevada to King's survey camp. After presenting a letter of introduction from a mutual friend, he begged for a job. He would help in any way he could. King hired him as an assistant topographer and general camp helper, for "nominal" pay—basically a "volunteer" (Brewer 1900).

But the gods soon smiled on Sereno Watson. Bailey, the official botanist, began to have health problems, so Watson became his assistant. When Bailey quit in early 1868, Watson was appointed expedition botanist, with a salary. It was the beginning of a successful and very satisfying life collecting and studying plants (3).

In early May of 1868, the expedition "took the field again and worked eastward from the Washoe through the Trinity, West Humboldt, Havallah, and the several other mountain ranges to Ruby River [possibly the Franklin River in the Ruby Valley], and from there the East Humboldt Mountains were explored" (Brewer 1900).

It was in the East Humboldt Mountains that Watson collected Petrophytum caespitosum. At that time, the East Humboldt range included the Ruby Mountains, which is where I saw it. Was the ghost of Sereno Watson nearby?

In his catalogue of collections, Watson provided a specific location: "Cliffs above Camp Ruby 7,000 ft." On my visit, I camped at the foot of the Ruby Mountains just 7.5 mi north of old Camp Ruby (also called Fort Ruby). I found the rockmat in a canyon immediately west. Sereno and I definitely were in the same area! And though I don't believe in ghosts, I do see them on occasion.

|

| Petrophytum caespitosum at base of limestone cliff, east side Ruby Mountains; October 2021. |

|

| Stems rise from clusters of leaves 3–12 mm long. |

|

| Inflorescences can be branched, but usually are simple cylindrical racemes. |

|

| Petrophytum caespitosum in a crack high up on the cliff (tip of arrow). |

|

| "The top of this two foot long plant is attached to the rock wall; the rest of the plant swings gently with any breeze." Photo ©Al Schneider, http://www.swcoloradowildflowers.com |

|

| Petrophytum caespitosum, with butterfly; Wasatch Range, Utah. Photo by Andrey Zharkikh. |

NOTES

(1) In Nuttall's day, "alpine" did not necessarily mean the highest elevations, above treeline. It was sometimes used for lower montane sites with no trees—a common situation in the arid American West.

(2) The genus is sometimes called Petrophyton, said to be an "orthographic variant (misspelling)".

(3) Among other things, Sereno Watson became Curator of Gray Herbarium at Harvard in 1888, a position he held until his death in 1892 (Coulter 1892).

|

| Sereno Watson, a "thorough and painstaking" botanist, working at Gray Herbarium (Coulter 1892). |

SOURCES

Once again, I'm immensely grateful to the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) for providing such easy access to original literature!

Brewer, WH 1903. Biographical memoir of Sereno Watson, 1820-1892. National Academy of Sciences. PDF

Coulter, JM. 1892. Sereno Watson. Bot. Gaz. 17:137–141, Plates VI, VII. Available online courtesy BHL.

Nuttall, T. 1840. Spiraea cespitosa in Torrey, J, and Gray, A. Flora of North America v. 1, 417-418, Available online courtesy BHL.

Rydberg, PA. 1900. Catalogue of the flora of Montana and the Yellowstone National Park, vol. 1:206–207. Available online courtesy BHL.

Watson, S. Catalogue of botanical collections made in Nevada and Utah, in 1867-9. Harvard University Botany Libraries. Available online courtesy BHL.

Williams, RL. 2003. A Region of Astonishing Beauty: The botanical exploration of the Rocky Mountains. Roberts Rinehart.