|

| Late afternoon at the Devil's Playground in northwest Utah—my kind of #vanlife. |

I ended my tour of Utah and Nevada last May with a stop at the Devil's Playground north of UT Highway 30 near ... well ... near not much of anything. It's at the south end of the Grouse Creek Mountains and about 40 air miles west of the north end of the Great Salt Lake. The Utah Geological Survey provides

directions here.

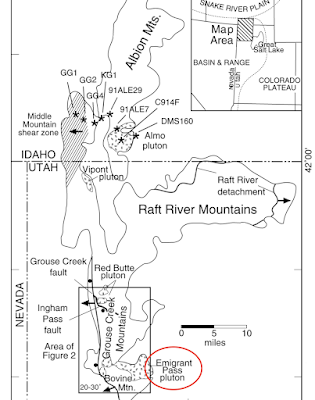

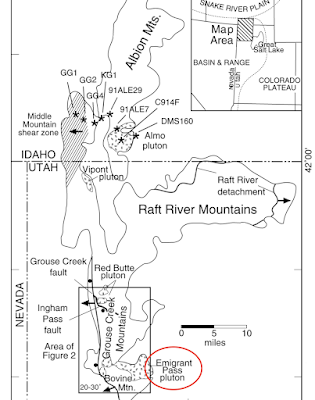

Like several other stops on the trip, this one featured an igneous intrusion—the Emigrant Pass pluton, emplaced 41 to 34 million years ago in three phases. Rock in the Devil's Playground area is part of the youngest phase (Egger et al. 2003). This pluton is especially interesting to geologists studying metamorphic core complexes (MCCs), for it is in the southern part of the Albion–Raft River–Grouse Creek MCC (ARG in map below).

|

| Black blobs are MCCs; arrow points to Emigrant Pass pluton. After Strickland et al. 2011. |

|

| Note multiple plutons in Albion, Raft River, Grouse Creek Mts. After Egger et al. 2003. |

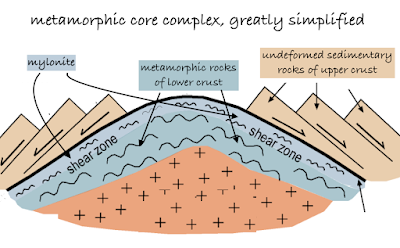

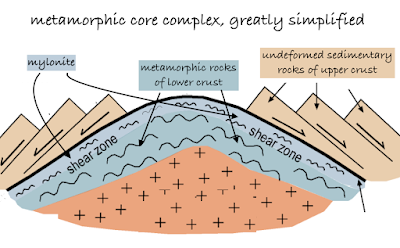

The diagram below shows a textbook metamorphic core complex (actually there may be too much variation to have a classic example). During continental extension, rock strata stretched, broke, and slid along low-angle faults, revealing older deeper rocks which domed upward. But continental extension has occurred across much of the Basin and Range Province

without making MCCs ... hmmm, puzzling.

|

| Based on Peterson & Buddington 2014, DeCourten & Biggar 2017. |

As I learned during my

trip to the Ruby Mountains, MCCs are controversial. Among topics debated is why they're clustered in this part of North America (thickened crust?). Another is the role of plutons in MCC formation. Some geologists argue that plutonism is the main driver, supplying heat that softens rocks and facilitates extension. After all, plutons roughly contemporaneous with extension "are ubiquitous in many of the core complexes" in this region. But other geologists disagree, arguing that plutonism plays a minor role at most (see Introduction in Egger et al. 2003 for more discussion).

I like metamorphic core complexes very much, largely for their mystery. But they're difficult. It's challenging just to spot one, even with a guidebook. These are giant structures, visible only as parts exposed here and there. Plutons are much easier to understand, fairly common, and yet still worth contemplating. I became a fan when I realized that if I can see a pluton, something dramatic must have happened.

|

| It seems plutons are often sculpted into intriguing forms, like the Harrison Pass pluton in the Ruby Mountains. |

|

Notch Peak intrusive at the base of the west face of the House Range; photo by Mike Nelson.

|

|

| Emigrant Pass pluton—a tilted world. Did it tilt during uplift? |

Plutons, like the god Pluto, reside in the Underworld. They form when magma solidifies well below the surface, where it cools slowly and forms visible crystals. So unless we make a

Dante-esque excursion miles underground, we can only see plutons if they've been exposed in some way. When the Grouse Creek Mountains rose about 13 million years ago, during Basin and Range extension and faulting (Ege 2006), erosion set in. That's probably when the "devils" of the Playground were born.

Rocks in this part of the Emigrant Pass pluton have been called granitic and granitoid. These are handy terms because the range of granitic rock types is broad and hard to subdivide neatly. Egger et al. (2003) are more specific: "a virtually homogeneous coarse-grained biotite granite". The granite is criss-crossed with aplite and pegmatite dikes, which formed when still-molten magma—hydrous and therefore last to crystallize—was injected into fractures in the solidifying pluton.

|

| Aplite is more resistant to erosion so dikes stick out a bit from the granite. |

|

| My field assistant pointed out a dike in a different kind of granitic rock. |

Weathering of the pluton may have started underground, with groundwater enlarging fractures. In any case, today's wonderfully enigmatic forms are largely products of physical and chemical weathering above ground (Ege 2006 explains this nicely). These processes will continue until eventually the alcoves, spires, arches, fins, and other devils disappear.

|

| Fine example of spheroidal or onion-skin weathering at the Devil's Playground. Photo courtesy scienceteacherexplorer (click link for more great shots). |

|

| Geocacher enjoying spheroidal weathering (source). |

|

| Are these young devils, recently emerged? Or elderly ones, to dust returning? |

|

| In the company of plants and rocks :) |

Among the devils were spring wildflowers, a nice touch. Perhaps the most common was

Stenotus acaulis, the Stemless Mock-goldenweed. It grows on rocky soils in drier areas across the western US. This is a DYC—"damn yellow composite"—but only because we find yellow composites difficult to identify. Seems to me that's

our damn problem.

|

| Stenotus acaulis; those of us who have been around for awhile may know it as Haplopappus acaulis. |

Another yellow composite (Compositae is the old name for the sunflower family) caught me by surprise—

Balsamorhiza hookeri, Hooker's Balsamroot, a plant of the Great Basin. I know Arrowleaf Balsamroot well, but didn't recognize this plant as a balsamroot. Based on online specimens and discussions, the plants here might be hybrids; more research needed.

Hooker's Balsamroot seems so different from Arrowleaf Balsamroot. Most strikingly, it is short (these plants are 10 to 15 cm tall), and can thrive on very dry rocky sites.

With so much sagebrush in the area, it wasn't surprising to find its common parasite—paintbrush; this one is

Castilleja angustifolia, the Northwest Paintbrush. The low gray-green shrub next to it in the photo is sagebrush. Like DYCs, paintbrushes are difficult to identify to species. But I've never heard anyone damn them. Thanks to markegger for the identification, via iNaturalist.

Paintbrushes are hemiparasitic. They can photosynthesize, but by tapping into sagebrush roots they grow more vigorously. This ability may vary among species, perhaps explaining conflicting reports online.

|

| Such a lovely parasite! |

Sources

DeCourten, F, and Biggar, N. 2017. Roadside Geology of Nevada. Mountain Press.

Peterson, J, and Buddington, A. 2014. A geological study of the McKenzie Conservation Area, Spokane County, Washington. Conference Paper.

Strickland, A, et al. 2011. Timing of Tertiary metamorphism and deformation in the Albion–Raft River–Grouse Creek metamorphic core complex, Utah and Idaho. J. Geol. 119:185–206.

https://doi.org/10.1086/658294

Thanks Hollis, of course i totally love this post. Did you know that initially (in my keeping of wild places journey) I did want study rocks? it is still there.

ReplyDeleteThanks, jozien :) Your comment showed up, but for some reason it was slow. I was notified by email well before it appeared here. I also had some trouble posting. Maybe blogger has recovered.

DeleteI hope you find ways to enjoy rocks!

Fascinating. Thanks for the simplified diagram/explanation of the metamorphic core complex. Beautiful wildflowers!

ReplyDeleteHello Beth ... Yeah, I had to sneak some flowers in, seems I've been totally caught up in geology recently.

Delete