|

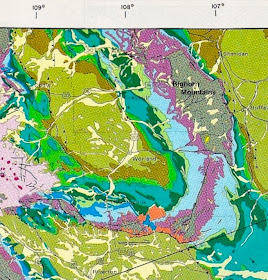

Geologic map of Wyoming; Love and Christiansen (1985); click image to view.

|

“A geologic map is a portrait of the surface of the Earth ... This map of Wyoming shows, in a very general way, the distribution of rocks and sediments across the face of Wyoming, scrubbed clean of its thin veneer of plants and soil. [horror of horrors!! ... italics added] From Wyoming Geomaps by Sheila Roberts, Geological Survey of Wyoming, 1989.This week is Earth Science Week and the theme for 2013 is Mapping our World -- to “promote awareness of the many exciting uses of maps and mapping technologies in the geosciences.” Geologic maps are indeed critical in my profession. But I’m not a geologist, I’m a field botanist. In Wyoming, we often rely on geologic maps to study plants.

I was lucky to start my career when the flora of Wyoming was still relatively poorly known. At times I felt like a 19th-century naturalist, roaming through unknown territory in search of new knowledge. The projects I enjoyed most were rare plant surveys. Many species then on Wyoming’s rare plant list were known only from a few specimens in herbaria. We had little clue as to their real status. Surveys were designed to answer the following: Is the species indeed rare? What’s its habitat? How widespread is it? Are there threats? Given limited funding and time, it was critical to maximize chances of finding populations. Often this required use of a geologic map.

|

Cary’s beartdtongue (Penstemon caryi) grows in areas underlain by calcareous rocks in the Bighorn Mountains. Photo by Andrew Kratz; courtesy USDA Forest Service.

|

Quite a few of our rare plants are edaphic endemics. Endemics are restricted to specific areas or habitats; edaphic endemics grow on specific soils or rock types. In Wyoming, they are especially common on calcareous rocks -- limestone and dolomite (yes, rare plants can be common, more discussion below).

|

| Wyoming rare plants endemic to calcareous habitat, by mountain range. |

Fortunately for rare-plant botanists, most mountain ranges in Wyoming have calcareous rocks exposed on their flanks. The following diagram of the Wind River Mountains shows why -- these are Laramide-style uplifts.

|

Section through Wind River Mountains; Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks exposed on northeast flank. Regional Geomorphology class notes; Dr. Brainerd Mears, Jr., Univ. Wyoming, 1984.

|

Below is a geologic map of the Bighorn Mountains and vicinity. The light blue map unit includes limestone and dolomite.

|

| Modified from Love and Christiansen (1985). |

Note the similar pattern in the next map. These are collection sites for rare plants endemic to limestone and dolomite -- calceophiles.

|

Map from Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD), 1988.

|

Obviously a botanist who understands and can use geologic maps will be better at rare plant surveys!

Shoshonea (Shoshonea pulvinata) grows on limestone, for example above the Clarks Fork Canyon in northwest Wyoming. Note round green patches in foreground of photo above. Surveying rare plants on the flanks of the Absaroka Mountains was one of my more spectacular projects. Photos above and below courtesy WYNDD.

In the right habitat, i.e. on the right rock type, edaphic endemics often grow in profusion. Sometimes it’s difficult to convince people that these really are species of concern.

Shultz’s milkvetch (Astragalus shultziorum) often forms extensive stands at the base of dolomite and limestone scree slopes in the Salt River Range. Photos above and below courtesy WYNDD.

|

| Flowers ca 12 mm long. |

Most or maybe even all of our edaphic endemics are thought to be neo-endemics (recently evolved), suggested by their restricted distribution and local abundance. When did they appear on the scene? Surely it was after the last ice age. During the Pleistocene much of Wyoming was in permafrost or under ice. We can only speculate of course, but what a wonderful thing to do while wandering in search of rare plants.

|

Aromatic pussytoes (Antennaria aromatica) occurs as scattered populations on limestone in mountain ranges in western Wyoming. The leaves smell of citronella or orange peels when crushed. Photo courtesy WYNDD.

|

v interesting! especially for a carbonate sedimentologist like me :) thanks..

ReplyDeleteNice to hear!

DeleteGreat post Hollis! I have to start paying closer attention to things other than all those rocks.

ReplyDeleteThanks so much, Jack. These rare plants that grow only on specific rock types have always fascinated me. They must have stories to tell re evolution and adaptation, but unfortunately we can't figure them out ... just yet.

Delete