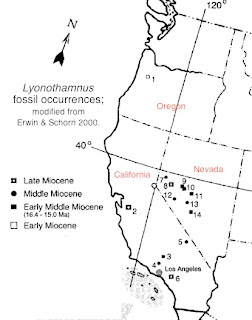

Recognize this tree? According to the fossil record, its close relatives were widespread in western North America during the Miocene, 23 to 6 Ma (million years ago). Fossilized remains have been found from Oregon south through western Nevada and California as far as what is now the Salton Sea (actually, the fossils were 300 km north of the Salton Sea when they were found because their chunk of California had moved that far north during the previous 12 million years). These trees were especially common in western Nevada; they were one of the dominant species at a lake in the Stewart Valley (14 Ma). The most recent fossils are dated at 6-7 Ma and no younger records of have been found. These trees apparently went extinct ... on the mainland that is.

In 1885, the great botanist Asa Gray described and published a curious new species of tree from Santa Catalina Island off the coast of southern California, calling it Lyonothamnus floribundus. The next year, E.L. Greene reported a closely-related species from Santa Cruz Island -- L. asplenifolius. These two trees now are considered to be related subspecies: Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. floribundus, the Catalina ironwood, and L. floribundus ssp. asplenifolius, the island ironwood or Santa Cruz Island ironwood.

These ironwoods are native only to the Channel Islands off southern California. The island ironwood, Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. asplenifolius, is found on Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Clemente Islands. It has compound fern-like leaves, hence the name “asplenifolius” ... “like asplenium” (a fern). The Catalina ironwood, L. floribundus ssp. floribundus, is native to Santa Catalina Island. It has simple (undivided) leaves, though leaves on sucker shoots occasionally show rudimentary division.

Left: The island ironwood, Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. asplenifolius, has compound leaves consisting of five long primary segments, each with many secondary segments. Note the distinctive parallel veins of the secondary segments, visible in closeup below.

Right: The Catalina ironwood, Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. floribundus, has simple leaves, though rudimentary division sometimes is seen in leaves on sucker shoots.

In the 1930s, it was discovered that Lyonothamnus wasn't just an island tree, that it once grew on the mainland. Fossils from Death Valley in southern California were reported by Daniel Axelrod, who continued to describe new fossil Lyonothamnus locations in California, Nevada and Oregon into the mid-1990s. The distinctive leaves and venation (arrangement of veins) of Lyonothamnus make fossils relatively easy to identify. The fossilized leaves below clearly have long narrow primary segments with many secondary segments, and the best preserved fossils show the characteristic venation as well (closeup on right). All fossil Lyonothamnus have compound leaves, similar to those of the island ironwood, suggesting that this is the more common form and that the simple leaves of the Catalina ironwood are a relatively-recent evolutionary development.

The island ironwood, with its beautiful fern-like leaves and red-and-gray shaggy bark, is becoming popular in landscaping, so one doesn’t need to travel to the Channel Islands to see it. I found it growing in the San Luis Obispo Botanic Garden in El Chorro Park. It is well-represented in the Channel Islands area of the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, and in fact is part of the SBBG logo. Island ironwood is the official tree of Santa Barbara County.

|

| Island ironwood growing on the Cal Poly campus in San Luis Obispo, California. Photo courtesy Cal Poly Plant Conservatory Tree Project. |

Island ironwoods belong to the rose family, confirmed by the small white flowers reminiscent of some other members of the Rosaceae, such as spiraea. While there is agreement among plant taxonomists regarding family assignment, the relationship of Lyonothamnus to other members of the rose family is not at all clear. Perhaps this genus is sufficiently ancient that it lacks close relatives, making classification within the family difficult (Morgan et al. 1994). Photo below courtesy Karduelis via Wikimedia Commons.

Of course the really interesting question is: Why are there still ironwoods on the islands but not on the mainland? We don’t really know and can only speculate, but that’s ok ... informed speculation is fun!

|

| Native populations of Lyonothamnus spp. indicated in blue. |

First, how might these trees have reached the Channel Islands from the mainland? The islands are high points of ridges that are mostly underwater. When I was a botany student in Santa Barbara oh-so-long ago, the thinking was that during times of glacial advance, sea level dropped enough to expose continuous ridges from the coast. Subsequent sea floor mapping killed that idea. Though sea level did drop sufficiently to connect some of the islands, there were no bridges to the mainland during the Pleistocene. And the Pleistocene was recent -- less than 1 Ma -- while the fossil record suggests that Lyonothamnus may have disappeared from the mainland as far back as 6 Ma.

Perhaps these trees are relics of an even older time ... back when the Coast Ranges were being uplifted (starting 30 Ma), and before the Western Transverse Ranges rotated almost 90º, sticking the westernmost peaks out in the ocean. Maybe ... but given the almost-intractable complexity of coastal California geology, I’m not going any further with this idea.

Why did Lyonothamnus disappear from the mainland? On Santa Cruz Island, ironwoods occupy a narrow range of habitat -- “primarily north-facing coastal slopes, often along small faults” and often on sites with cold-air drainage (UCNRS 2007). Perhaps Lyonothamnus thrived on the mainland in cooler wetter environments of the past, disappearing as the climate warmed. Somehow it managed to persist in these island refugia.

That’s fortunate for us! Lyonothamnus, missing for 6 million years until Santa Barbara resident Barclay Hazard discovered it on Santa Cruz Island in 1885, is still with us. When we look at these trees, we can imagine woodlands of 15 million years ago, and marvel at ironwood-dominated landscapes where now there is desert. It is this ability to peer into past worlds, even if only dimly, that makes fields such as plant geography, paleontology and geology so exciting.

Sources (in addition to links in post)

Erwin, D.M. and Schorn, H.E. Revision of Lyonothamnus A. Gray (Rosaceae) from the Neogene of Western North America. Int. J. of Plant Sci. 161: 179-193.

Morgan D.R., Soltis, D.E., and Robertson, K.R. 1994. Systematic and evolutionary implications of rbcL sequence variation in Rosaceae. Am. J. Bot. 81:890–903.

Smith, C.F. 1976. A flora of the Santa Barbara region, California. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Thorne, R.F. 1967. A flora of Santa Catalina Island, California. Aliso 6:1-77.

University of California Natural Reserve System. May 2007. Santa Cruz Island Reserve Brochure. http://santacruz.ucnrs.org/SCIR%20brochure%20text%204=2007.pdf [accessed May 2012].

I've heard of ironwood but this is the first time I've seen its (beautiful) leaves.

ReplyDeleteThe leaves really are striking -- I saw more yesterday around an outdoor restaurant on the coast, beautiful.

DeleteGreat post, just saw it out on Santa Rosa and was surfing for some good info. I appreciate the effort you took to put this together!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Michael -- for visiting and for the Comment. I found your blog, looking forward to reading about/seeing Santa Rosa.

Deleteinteresting post and fascinating about the apparent ancient occurrence of lyonothamnus in Oregon. certainly it grows well and looks beautiful in my garden near Bandon on the "upper" southern Oregon coast along with another "channel island" ancient relict plant quercus tomentella/island oak. both tolerate some frost and snow, heavy winter rains and summer drought (moderated by near coastal conditions and low heat accumulations) and do well with little or no care after initial establishment.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Anon. Ancient relic plants are intriguing to me. We have nothing like that here in Wyoming, at least that we know of. Lots of neoendemics though.

ReplyDeleteas they (relicts) are to me. many of the plants on my property are selected from my study of Daniel Axelrod's flora lists from the Miocene of western California most especially what he terms the "oak-laurel" and "mixed evergreen" forests with species of umbellularia, Persia, lyonothamnus, arbutus, clethra (Mexicana), myrica, lithocarpus, prunus (evergreen) and numerous evergreen oak species (tomentella, agrifolia, chrysolepis, wislizenii, virginiana, emoryi, brandegeei, engelmannii, etc.). would assume that where you are you could "recreate" the ancient arcto-tertiary mixed hardwood forest with species of acer, quercus, populous, platanus, juglans, salix, celtis, ulmus, etc. thanks for responding and enjoy reading your blog posts. "anon" (georgeinbandonoregon)

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading, George, and for your comments! (sorry, I didn't catch this one until now). Sounds like a really neat project you have going there.

DeleteI both and planted two Iron Trees from the Santa Catalina Island.

ReplyDeleteThose trees are now big-monumental beautifying my backyard in Monterey, CA.

Sounds wonderful, Anon! Thx for visiting

DeleteGreat article! Here in Europe we have some similar discoveries on mediterranean islands. Do You know where to get seeds??

ReplyDeleteRegards, Berndt (Germany)

Berndt, I don't know where to get seeds. But I have seen this ironwood in landscaping, so seeds must be available somewhere. Thanks for visiting!

DeleteI loved reading this account Hollis. It is esecially well written, illustrated and researched. Thank you. It touches on dryland plant survival, one I am writing about for a journal. As I live on an ancient and very dry continent (Australia) rocks, fossils, plant survival and tress are of great interest to me. Do you know if this Genus is fire adapted eg has lignotubers? It does have viable seeds and these may be enough.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Eugene! I wouldn't be surprised if Lyonothamnus were fire adapted given the location -- Mediterranean California -- but I don't know about specific fire adaptations. If you haven't already, it might be useful to contact a grower, e.g. https://www.smgrowers.com/index.asp

DeleteThank you Hollis. Will do when I have some time.

Delete