|

| How many Rosaceous fruits are in this painting? Answer at end of post. (Still Life with Fruit by Severin Roesen, 1852; Smithsonian Open Access) |

The Rosaceae is a large cosmopolitan family of plants, with c. 3000 species scattered across every continent except Antarctica. It's best represented in the Northern Hemisphere, mainly in temperate habitats. This is a family much loved by humans. Gardeners have grown the "queen of the flowers" (the rose) for at least 5000 years, and we've enjoyed the diverse delicious fruits even longer.

Members of a plant family, even a large one, are supposed to be similar and often they are. For example, flowers of the vast majority of species in the Rose Family (excluding ornamentals) have five showy-but-simple petals surrounded by five green sepals. Inside the petals are numerous pollen-producing stamens surrounding one-to-many ovaries, each of which contains one or two ovules awaiting fertilization.

|

| A typical Rosaceous flower: 5 sepals (green tips visible), 5 petals, many stamens (anthers at tips), and a cluster of numerous ovaries. (Wild Strawberry, Fragaria virginiana. Matt Lavin photo) |

Unlike the flowers of the Rose Family—so similar and so simple—the fruits are diverse and often complex, in fact notoriously so. For centuries botanists have tried to subdivide the family based on fruit type. They've always failed.

By definition, fruits are mature ovaries containing mature ovules (seeds). But there can be so much more—thick flesh, plumose tails, tough skins, rock-hard coats, accessory structures, and aggregation. The Rose Family includes all of these! Though this diversity frustrates plant taxonomists, the rest of us can enjoy it :)

It would be foolish to try to cover the full range of Rosaceous fruit diversity. Readers would begin to fall away less than halfway through. Instead here are some favorites, starting with complicated and delicious types, and finishing with one that's quite simple and not at all tasty, but spectacular in its own way.

But first ... do you know which Rosaceous fruit type is most widely consumed by humans?

|

| Our favorite fruit in the Rose Family is a pome, from Old French "pome" meaning apple (source). |

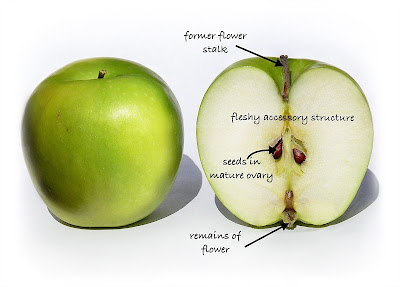

Malus domesticus, the domestic apple tree, probably originated in the mountains of Central Asia. Now it's represented by thousands of cultivars grown in temperate regions worldwide. The apple itself is a pome, which botanists define as a fruit with "a central core containing multiple small seeds, which is enveloped by a tough membrane and surrounded by an edible layer of flesh." Technically speaking, the thick fleshy layer is an accessory structure.

Slicing an apple in half lengthwise shows how evolution elaborated on the basic seeds-in-mature-ovary structure in creating the pome.

The pome is unique to the Rose Family, but not just to apples. Pears and quinces also bear pomes, as do many native species. Their pomes are small, but look closely—they are indeed tiny apples.

|

| Pomes of four species of hawthorne (Crataegus), c. 1 cm diameter; by Nadiatalent. |

Another popular fruit type with a delicious accessory structure is the drupe, also known as stone fruit.

|

| Domestic cherry—one of many delicious drupes in the Rose Family (source unknown). |

The genus

Prunus includes what appears to be a diversity of fruits: cherries, plums, peaches, nectarines, apricots, and almonds! But in fact they all are drupes, defined as "fruit in which an outer fleshy part surrounds a single shell (the pit or stone) with a seed (kernel) inside" (

source). [Unlike pomes, drupes are not limited to the Rose Family. For example, olives and dates are drupes.]

|

| The almond tree, Prunus dulcis, also bears drupes. The almond itself is a seed (source; labels added). |

Drupes are well represented in the wild, for example our many species of wild cherries.

|

| Harvest time! Chokecherries, Prunus virginiana, by Matt Lavin. |

|

| "Thousands of drupes readied to make chokecherry whatever" says Matt. Would that be jelly? wine? |

Now we advance to a higher level of complexity—a fruit that develops from

multiple ovaries of a

single flower. A tasty but controversial example is the strawberry (actually not a

berry but that's not the controversy).

|

| Wood Strawberry, Fragaria vesca (Jakob Sturm, 1798, BHL via Flickr). Question added. |

Strawberry flowers are typical of the Rose Family (see above). But after fertilization, things get interesting. The many ovaries, each containing a single ovule, mature to become achenes—dry one-seeded fruits (

g/G in illustration). At the same time the flower base (receptacle) grows, becoming a red mass of yummy flesh with the achenes embedded on its surface (

f in illustration).

Herein lies the controversy: What is the fruit of the strawberry? Is it the fleshy globe adorned with achenes, or the achenes themselves? Some botanists rage over this, insisting achenes are the true fruits (

in Wikipedia for example). Others think this silly, and simply refer to strawberries as aggregate fruits (my preference).

|

| Young strawberry, with styles still present on maturing achenes (Olivier via Flickr). |

|

| Wild Strawberry, Fragaria virginiana (JW Frank via Flickr). |

As promised, the final fruit is simple but beautiful—a single achene, specifically that of Mountain Mahogany (genus

Cercocarpus). These shrubs and small trees of the arid American West are members of the Rose Family. But no matter how long one stares at their little flowers, it's hard to see roses.

|

| Flowers of Birchleaf Mountain Mahogany (C. betulifolia) are just 5 mm across and have NO petals. The sepals form a cup with many stamens surrounding a single pistil (Joe Decruyenaere via Flickr). |

A Mountain Mahogany flower may be humble, but not the resulting fruit. The pistil and its ovule become an achene with a long persistent feathery style, ready to fly with the wind. En masse, these "seed tails" transform the plant that bears them.

|

| Fruits of Mountain Mahogany (C. montanus) preparing to launch; seed tails to 8 cm long (Matt Lavin). |

|

| Mountain Mahogany transformed by seed tails. Achenes can be spectacular! (C. ledifolius, Matt Lavin) |

Now we return to where we started—"How many Rosaceous fruits are in Roesen's painting?" The answer is "many" (exact number depends on your opinion regarding aggregate fruits). I found pomes (apples), drupes (peaches, plums, cherries, maybe nectarines), aggregates of drupes (blackberries), and aggregates of achenes (strawberries). Did I miss anything?

This has been quite a long post, I agree. But I would be remiss if I were to omit Robert Frost's thoughts on the subject.

Sources (in addition to links in post)

Rosaceae in Flora of North America, which includes a list of fruit types:

"... achenes aggregated or not, follicles aggregated or not, drupes aggregated or not, aggregated nutlets, pomes, aggregated drupelets, or capsules; sometimes involving accessory organs, for example, hypanthium, torus."

Haywood, VH. 1978. Flowering Plants of the World. Oxford University Press.

Judd, WS, et al. 2002. Plant Systematics, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc.