|

|

Carnegie Building in Laramie, home of the Albany County Public Library for 75 years. American Heritage Center, U. Wyoming; date unknown (but note the style of the women's clothing).

|

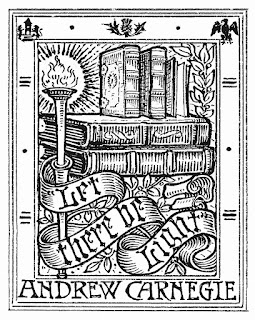

[This is my December contribution to the Laramie Boomerang’s “Living History” column. It's not about botany or geology, but something equally important: public libraries. Laramie's first library building was a gift from the man who did so much to establish public libraries in the US—Andrew Carnegie, robber baron turned philanthropist. It served as a library for 75 years, and there still are many residents who remember it fondly. Is there a Carnegie Library in your life?]

On January 22, 1906, some 150 Laramie citizens left winter outside and climbed a flight of heavy oak stairs to the second floor of the new building at the corner of Fourth and Grand. In the warm well-lit lecture room, they listened as civic leaders spoke proudly, eloquently and at length about the Albany County Public Library, now housed in its own building—a gift of one of the wealthiest men in the world, Andrew Carnegie.

POVERTY TO PHILANTHROPY

Carnegie was born in 1835 in Scotland, son of a successful weaver. But when mechanization made his father’s skills obsolete, the family fell into abject poverty. In 1848 they immigrated to Pittsburgh, where Andrew and his father both found jobs in a cotton factory. In just twenty years, Andrew rose from “bobbin boy” at $1.20/week to steel magnate worth $400,000. He went on to become one of the “robber barons” of the Gilded Age—men who made millions by monopolizing rapidly-growing industries.

In 1901, he sold his business for $480 million to banker JP Morgan, who declared Carnegie to be “the richest man in the world.” Carnegie then turned to what he considered a duty of the wealthy—philanthropy on a grand scale. By the time of his death in 1919, he had donated 90% of his fortune.

|

|

“Andrew Carnegie in Colors” from Life magazine, April 13, 1905. A month later Life wrote: “no American has ever before given away money for philanthropic purposes on the scale that Mr. Carnegie is doing.” Hathitrust.

|

During his lifetime, Carnegie contributed to 2500 public libraries in the U.S. and abroad. Most were in smaller communities where they had more impact. He donated specifically for buildings, but only if the library were free to the public, and the community guaranteed annual support and a site free of debt.

LOTS OF BOOKS BUT NO HOME

In 1902, U.W. Professor Aven Nelson and Albany Co. National Bank Cashier Eli Crumrine discovered they had the same terrific idea—ask Andrew Carnegie to pay for a building for Laramie’s library. For 30+ years it had moved among various private and commercial locations, none of them satisfactory. Carnegie recently had given $50,000 to Cheyenne for a library building, surely he would do the same for Laramie!

They prepared a five-page letter, dated May 2, 1902: “Honored Sir: Your well known desire to help your fellow men by planting libraries here and there throughout the world has reached to the outmost parts of the earth …” [after lengthy accolades they got to the point] “… we earnestly appeal to you for the creation in this city of a $50,000 library building.”

They provided evidence justifying their request. “Laramie is now a city of more than 8,000 people” with all indications of permanency: excellent water and sewerage systems, and a modern fire department. “It is the education center of the state,” site of Wyoming’s only university. As “the center of influence for a large rural population” it benefits twice as many people as in the city itself. The City already has a free public library; in fact, Laramie’s “collection of books is second to none in the state” but is kept in “cramped, unsuitable and uninviting quarters.”

The letter ended with a plea: “Hoping that you may find time to look into the merits of our petition and that we shall soon have the pleasure of receiving from you a communication looking toward the ultimate fulfillment of our earnest desires” [italics added]. But they were overly optimistic.

DISAPPOINTMENT

Months went by. In October they wrote James Bertram, head of Carnegie’s library program. “We are very anxious to know whether the matter has yet been called to the attention of Mr. Carnegie. Thanking you for an early reply …” Still they waited.

The decision arrived January 2, 1903. Bertram’s letter was short. If the community would “maintain a Free Public Library at a cost of not less than Two Thousand Dollars a year and provide a suitable site, Mr. Carnegie will be glad to furnish Twenty Thousand Dollars to erect a Free Public Library for Laramie.”

More than a little disappointed, Nelson and Crumrine fired off another letter: “Deeply grateful for the worthy beneficence you accord to our city, we yet venture to beg … you to do still more generously by us.” They dropped their request from $50,000 to $40,000, but not before mentioning Carnegie’s more generous gift to Cheyenne.

Bertram wrote back explaining that new rules required communities to provide annual funding at a rate of 10% of the gift. Laramie had promised $2000 annually, therefore they would receive $20,000 for the building. This still was a generous offer (about $600,000 today), and one they couldn’t refuse.

NEXT STEPS

On February 26, 1903, citizens filled the County Courthouse, eager to learn if there would be a Carnegie Library in Laramie. A resolution to accept Carnegie’s offer of $20,000 was presented. The County would need to raise $2000 annually for support, requiring a tax increase of about 50¢ on each $1000. This didn’t dampen the obvious enthusiasm in the room.

W.H. Holliday, representing Laramie businessmen, endorsed the resolution, as did University President Smiley, who hoped the library and possibly a game room would “counteract the bad influences of some other places upon the students.” Mrs. [Mary] Bellamy stated that the Woman’s Club favored accepting Carnegie’s offer, and added that girls “read two thirds more than boys and the library would be of more benefit to them.”

A vote was called. After the resolution passed almost unanimously, the County Commissioners appointed a Library Building Commission composed of Crumrine, Nelson, and W.H. Holliday. It was agreed that the City would purchase a site to donate to the County, preferably near the courthouse so that if interest in the library waned, Carnegie’s building could be used as a jail.

The City purchased a lot at Fourth and Grand from “Grandma Black” who owned a rooming house there. At $2500, it was a bargain. After the property was duly transferred to the County, Aven Nelson drew and circulated a sketch of the desired building. New York architect Henry D. Whitfield’s plan was chosen. He said it could be built for less than $20,000, even at New York prices, which were 25% higher than in Laramie. Thus assured, the Building Commission put the project out for bid.

On August 11, 1903, a Boomerang headline announced the bad news: “Lowest Bids Amount to Far More Than Sum Donated.” In fact, total cost would exceed Carnegie’s gift by $10,000! The Building Commissioners contacted Whitfield, who sent a revised plan. Bids were again solicited.

Two months later, the Boomerang had good news: “Something definite has been accomplished at last, in regard to the building of the Carnegie library—the contract has been let.” The three bids were remarkably close, ranging from $18,250 to $18,770 total. Also remarkably, the lowest bid was submitted by W.H. Holliday, President of the Building Commission. He got the contract.

Construction was completed two years later at a cost of $20,077 (Crumrine paid the $77 overage). Furnishings were not included, so a “Library Fair” was held featuring a play, baby show, supper with an “overwhelming menu” for 25¢, and a formal ball following a grand march led by “King” Edward Ivinson. Well-attended, the event raised $825.20.

LIBRARY DEDICATION

On January 24, 1906, the front page of the Boomerang was devoted to the Carnegie Library dedication ceremony two days earlier. “The spacious auditorium was crowded to its limit with the representatives of the intelligent citizens of Laramie. The addresses of the different able speakers were received with great pleasure, not only for their oratorical value, but for the multitude of good common sense statements …”

On January 24, 1906, the front page of the Boomerang was devoted to the Carnegie Library dedication ceremony two days earlier. “The spacious auditorium was crowded to its limit with the representatives of the intelligent citizens of Laramie. The addresses of the different able speakers were received with great pleasure, not only for their oratorical value, but for the multitude of good common sense statements …”

The ceremony began with a “musical treat” by Graeppe’s orchestra, followed by “a very eloquent and heartfelt prayer” by Reverend R.A. Lansdell. The main address—History of the Carnegie Library Building—was delivered by Aven Nelson. Several prominent citizens then spoke more briefly.

The popular song “Daddy” was artistically rendered by the well-known (in Laramie) singer Mrs. Trumbull, ably accompanied by Miss Laura Lee. The Boomerang reported that “her beautiful contralto voice was never before heard to a greater advantage … clear and sweet and what made it more pleasing was her perfect enunciation.” But she refused the call for an encore.

Bishop Keane then spoke, stressing that citizens “should never give a poor book or indifferent book to the library.” That way the quality of the holdings would be maintained. But the bishop was not without wit. “All good works were done on the heights,” he said, “and Laramie is high.”

After an original poem read by Judge Groesbeck and a few remarks from the audience, W.H. Holliday presented the library keys to County Commissioner Nellis Corthell, who, after accepting them, said the library did not need keys. So Mr. Holliday received them back.

CARNEGIE BUILDING TODAY

Most Carnegie libraries were successful, and often outgrew their buildings. Some were expanded, but many were torn down or repurposed. The Albany County Public Library moved to its current location at 310 S. 8th St. in 1981. Fortunately the Carnegie Building was not demolished, nor did it become a jail as some had contemplated in 1903. It now houses City offices. But the spirit of the old library still resides in the entryway, in the form of an exhibit about Carnegie and his contribution to our community. The original “bronze medallion of our benefactor” looks down from a wall near the reception desk.

|

| Andrew Carnegie; source. |