What lies on the counter does not lie,

utters no false word, speaks volumes …

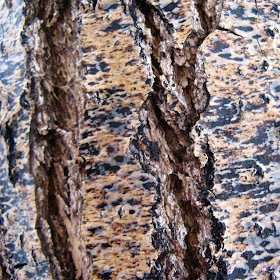

The edge of an indurated ash spear point says,

100,000 years ago some man he sat here flaking,

grunting, bleeding, thinking.

An iron cast of an iron ball in a lunar-like crater

but younger cretaceous only a place

Rhombohedral calcite crystal, rhombohedrally needs to be

picked up, felt about with fingertips looked at clear through,

dirty, cloudy, angled, morphed and helpless.

(I could have been an evaporite without a tongue!)

A polished black chunk of Nama Dolomite fits ripe

in the palm, a coral brain, formerly sentient rock?

sandblasted a million years, can no longer talk.

(rock as a memory repository?) Spin, spin, spin ___.

from Carolina’s phosphate, dug up by the dozer load.

Dangerous sea. Hear the scream. Munch münch.

Professor in a white suit in full moonlight

stole the fallen meteorite, that sits on a trilobite

from older hills, (“in this country,”

‘ol Spit Chin said, “you can be your own granddad.”)

(“when I first got that rock I slept with it”)

Jesus is the name of the trilobite.

|

| Trilobite Jesus |

Rising from that space rock, a magnet tower

from the toy store, where the Toy Store Guy

stood behind a display of force at a distance

that made my head ice cream and leap with joy

like a circus porpoise, like the tautness of air

pushing air pushing on the counter one magnet

against another - from a distance - is magic.

Pieces of air and small spaces between the pieces,

(at the super bowl party I dropped the pizza.)

A bowl turned by Old Sir John-On-The-Lathe,

died 1845? Everyone spins his tops, like magnets

they attract thoughts of places that show

the possibility of balance on a planet spinning,

slowly slowing down, begun to wobble—

and so reveal: The Reasons for the Seasons.

The Fall will come, that’s for sure, the wobbler

will wobble off the counter through the floor

to the center of a star – Fall In >< Fall Out – mind

goes supernova: the heat of molecular feeling felt.

Imagine, a white sand beach:

the pier you take evenings for a drink, (below,

small cilia undulate to and fro in pulsing waters)

you think: attach to pier, synthetic barnacles;

spin, spin, spin, and so, Monkey Man learns

• • •

Geologist and poet Danny Rosen lives in the Grand Valley of western Colorado, in a house filled with geological mementos. He is founder of the Lithic Press—an independent press publishing, primarily, books of poems—and recently opened the Lithic Bookstore and Gallery in downtown Fruita.

|

Rosens at the Counter, Danny supervising.

|