|

| Strolling down a river ... |

Our fall was unprecedentedly mild—so much so that on December 9, I returned to the Pawnee Buttes in northeastern Colorado (see recent geo-challenge) to hike to the crest of Lipps Bluff. I wanted to walk where rhinos walked, stroll where camels strolled, and pause where oreodonts paused to drink.

|

Restoration of Merycochoerus, an oreodont, by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913. It's also called a ruminating hog, though not closely related to pigs.

|

The Pawnee Buttes and Lipps Bluff are relics of a time when the High Plains extended further west. In fact, about five million years ago the Plains reached all the way to the Rocky Mountains. Since then the South Platte River and its tributaries have cut down, eroded and carried off enough material to create the Colorado Piedmont, a lower area between the Rockies and today’s High Plains. [The Gangplank in southeast Wyoming is an exception.]

|

The Pawnee Buttes are in the northeast corner of the Colorado Piedmont, close to the High Plains. Map modified from Trimble 1980.

|

Escarpments mark the edges of the retreating High Plains. Sometimes buttes and ridges stand nearby—isolated remnants spared by erosion.

|

High Plains Escarpment northwest of Pawnee Buttes. This is wind country, shown by turbines above the escarpment and dark orthogonal lines below—tumbleweeds caught on barbed-wire fences.

|

|

Lipps Bluff and Pawnee Buttes stand above the Colorado Piedmont; High Plains Escarpment visible in the distance between the two buttes.

|

Harder rocks cap the Buttes and Bluff, slowing erosion. They're made of river deposits—gravel, sand and silt. In other words, the remains of a stream bed now form the high points of the landscape. This is a great example of topographic inversion.

Inverted topography is an awesome thing. To look down a 20-million-year-old stream bed, now 200 feet above the valley bottom, feels magical! It's experiences like this that make geotripping so exciting.

|

Sediments deposited by a stream roughly 20 million years ago now form the top of Lipps Bluff.

|

When I visited last spring, the Lipps Bluff trail was closed to protect nesting raptors (March 1 to June 30 every year). So I made another trip to check out the rocks on the crest. It was a short hike—maybe two miles roundtrip. But if you go, allow plenty of time for geo-gawking, plant appreciation, view-inspired contemplation and time-travel.

|

Lipps Bluff from the trailhead; tops of Pawnee Buttes visible behind on left.

|

|

On a map of old trails and settlements in northeast Colorado, West and East Pawnee Buttes are inexplicably labeled Devils Smoke House and Gabriels Castle (Scott 1989).

|

The rocks capping the Buttes and Bluff are part of the Ogallala Group, which also covers the High Plains (but often buried under recent deposits). It's the uppermost part of a giant wedge of sediments eroded off the Rocky Mountains and deposited to the east. The Ogallala Group represents the last of three major pulses of erosion and deposition, and the most extensive—reaching as far as eastern Nebraska and south across Texas. Deposition took place roughly 19 to 5 million years ago (Miocene).

|

Three major pulses of deposition of material eroded from the Rocky Mountains (Trimble 1980). The Ogallala occurs not just in the yellow area, but also on top of the older orange and brown units.

|

Being stream deposits, Ogallala sediments are heterogenous, ranging from fine silt deposited in slow waters to large cobbles or even boulders in raging torrents. Sequences are complex. Sediment size can change dramatically even in one place through a single year. And Ogallala rivers shifted around. Rivers move by cutting into banks, depositing sediments, and sometimes abandoning a channel entirely. Years later they may return, cutting into sediments they deposited earlier. So figuring out Ogallala rocks takes a lot of time and effort—like working on a puzzle with seemingly endless pieces, many of which have the same pattern but aren’t from the same part of the puzzle.

“The simple notion of sedimentary rocks as flat uniform strata, commonly called layer-cake stratigraphy, is completely inadequate to unravel the detailed history of these sediments.” —Maher & colleagues (2003) on Tertiary sediments of the Great PlainsFortunately for geotrippers, the Ogallala Group has received a lot of attention in the Pawnee Buttes area. See papers cited below, as well as Recommended Reading at the end of the post for more on the larger context.

The gray rocks atop Lipps Bluff are part of the Martin Canyon Formation—the basal unit of the Ogallala Group here (Tedford 2004, Prothero & Dold 2008). They’re lithified stream sediments deposited in a valley that extended east into northwest Nebraska (Scott 1982). They rest unconformably on siltstones of the Oligocene White River Group. Apparently the intervening Arikaree Group is missing.

|

Unconformity between the Martin Canyon Formation and pale siltstones of the White River Group.

|

|

Martin Canyon outcrops look very much like stream deposits. Here’s a sandy bar, and layers of cobbles deposited during faster flow.

|

|

Stream-deposited cross-bedded sand(stone).

|

|

Siltstone nodules in a matrix of finer sediments.

|

|

Broken nodule reveals its concentric nature.

|

|

Nodules weathered out, ready to travel again.

|

Martin Canyon clasts are a mix of locally-derived sedimentary rocks like the siltstone nodules, and crystalline rocks from the Rocky Mountains. I found pieces of pink Sherman granite from the Laramie Range, my home territory.

Then there were the many puzzling patterns in the rock—do they say something about the river, the environment, subsequent processing? Do you know?

Occasionally I found patches of blackened coarse sandstone, also a mystery.

From a geological perspective, Lipps Bluff and the Pawnee Buttes are not long for this world. Their river-rock caps are falling apart, so they too will disappear into the Colorado Piedmont.

|

Erosion of the soft White River slope undercuts the Martin Canyon cap, and fragments fall.

|

|

A souvenir—a fallen chunk of coarse sandstone with siltstone nodules (12" tiles).

|

Why would the Ogallala Group be thoroughly studied in the Pawnee Buttes area? No, not for oil and gas (good guess though). It’s because fossils are abundant. And there are great fossil sites scattered across the High Plains, which means we know a fair amount about life during Ogallala times. So let’s time-travel to the “Martin Canyon River” back when it was water rather than rock.

The setting wasn’t all that different from the High Plains today. Just fill in the zillion tons of dirt excavated by the South Platte, remove the wind turbines, rewind any cultivation, and maybe tweak the composition of the sweeping grasslands that went on forever. It seems there was a more pronounced dry season during the Miocene (Maher & colleagues 2003).

|

Yuccas were common in Ogallala times, as they are today.

|

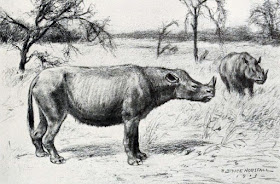

In the distance we would see herds of animals grazing—like the herds of bison of the recent past and cattle today. But if we hid among the hackberries along the river at dusk, we’d see that these animals are strangers. Rhinos, small camels, tiny horses, strange horse-like creatures with claws, and pig-like oreodonts would come to drink in the dim light, glancing up constantly, looking this way and that, watching for movement, ready to run from the dreaded bear dogs.

|

Small rhinos (Menoceras ) were common on Miocene grasslands. Restoration by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913.

|

|

Parahippus, an extinct relative of today’s horse, stood about a meter tall. Unlike its ancestors, it was a grazer and well-adapted to life on the plains. Restoration from a Smithsonian mural, 1964.

|

|

Another common inhabitant was Moropus, perhaps related to the modern horse, rhino, and tapir. In other words, it was odd. It had long claws for defense or maybe for digging. Restoration of Moropus threatening a pair of bear dogs, by Jay Matternes.

|

|

Daphoenodon was a large bear dog (not a canid), a long-legged pursuit predator adapted to the open plains. Restoration by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913.

|

Recommended Reading

The High Plains: Full of Character provides an excellent summary of the bigger picture—the High Plains in the context of the Great Plains.

Roadside Geology of Nebraska (Mayer & colleagues 2003) gives lie to the belief that Great Plains geology is boring. And it’s not your typical roadside geology guide. It starts with a thorough introduction, and includes detailed descriptions of areas of interest.