|

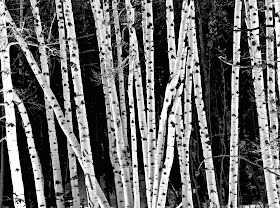

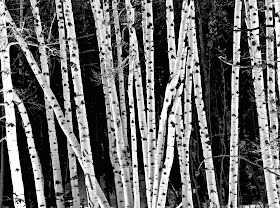

| Aspen. |

There’s a photographic world somewhere between realism and pure abstraction where I love to be. Traditional subjects are secondary, upstaged by things usually overlooked: light, form, pattern, arrangement.

These become the subject, the message.

|

| Aspen. |

“abstract photography concentrates on shape, form, colour, pattern and texture. ... The subject of the photo is often only a small part of the idea of the image.” Photokonnexion, Abstract Photography

“It strives to deviate from realistic reproductions and focuses on creative expression instead. Familiar subjects are shown in a new and unique light, and although we may not immediately identify them, we are entranced by the beauty of their shapes, colors” Kristine Hojilla, The Art of Abstract Photography

|

| Aspen. |

“Realism and abstraction can be seen as the two ends of a continuum. On one end, photographic realism mimics the appearance of a recognizable subject. On the other is non-objective abstraction that resembles nothing but itself.” Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Realism + Abstraction

|

Non-objective abstract aspen.

|

I think there's an inherent realism in photography. After all, one of the earliest uses was documentation – reproducing scenes for those who couldn’t be there to see for themselves. How wonderful those first photos must have seemed … so much more powerful than written words!

As technology and skills improved, photos became art as well as documentation. Photographers thought more carefully about light, arrangement, framing. And they experimented. It wasn’t long before they were shooting abstract compositions.

Yet some would argue that all photographs are abstract because we make choices: the subject itself, how much to include, point of view, exposure, depth of field. Interesting debate … fortunately we don’t have resolve it to enjoy abstract photography.

|

| Realistic banana leaves in an abstract photo. |

How do we reach the wonderful other-world of the abstract? There are many paths ... let's explore a few.

“The power of observation is important … look more closely at everyday objects we would otherwise ignore, and find the beauty and the ‘interestingness’ in them” Kristine Hojilla

This is the greatest pleasure for me – looking more closely, finding ‘interestingness’. View the subject from all angles. Frame with the viewfinder. Zoom in. Spend hours in one place and leave with a far greater appreciation and understanding than eyes alone would provide.

“By disciplining your eyes to see things, not as whole units, but as colors, patterns, textures and lines, you can experiment with limitless possibilities.” Clive Branson, Abstract Photography Up Close

Sometimes it’s helpful to consciously ignore the subject. Look instead for lines, shapes, colors, patterns and other details.

“Often the image will not be a literal view of the subject itself ... The impact of aspects of the subject become a form of expressing the point. The abstract tends to bring out some or all of these aspects” Photokonnexion, Abstract Photography (they list 21 aspects to look for – treasure hunts!)

|

Light, color and detail in heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia).

|

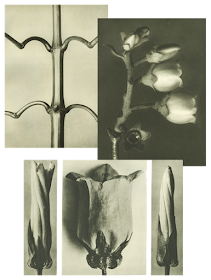

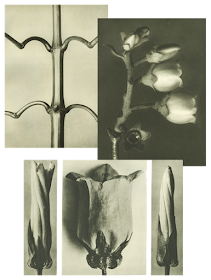

Plants make great abstract subjects. They’re full of of lines, shapes, contrasting colors and intriguing details. Some of the earliest abstract photos were of plants. Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) was fascinated with their “totally artistic and architectural structure”. He collected specimens, brought them home, and shot macro photos with his

homemade camera. The level of detail he achieved is astounding, and his images are exquisite.

Historians disagree on Blossfeldt.

Lyle Rexer considers him an early abstract photographer;

others assign him to the New Objectivity movement. If we could somehow ask Blossfeldt himself, he might shake his head in puzzlement. He used the photos as visual aids in his

Live Plant Modeling class at the Royal Museum of Arts and Crafts (his specialty was decorative architecture). Only later did they become art.

|

From Impatiens, Vaccinium, and Convolvulus by Karl Blossfeldt. Original images here.

|

In a sense, Blossfeldt’s photos are hyper-realistic. Yet they feel abstract because the subjects are out of context, and enlarged to show details not normally noticed. Zooming in or cropping can have the same effect, minimizing the context and directing the viewer to features chosen by the photographer.

“crop tightly using the whole frame, emphasizing color, texture or pattern … remove everything that does not, in some way, strengthen the viewer’s emotional reaction.” Clive Branson

Even if it isn't tightly cropped, a photo can feel abstract if the arrangement is unusual.

|

Edible fig (Ficus carica).

|

|

| Wild sunflower (Helianthus annuus). |

Abstract photography is sometimes described as the “art of subtraction” – minimizing content, simplifying.

|

Remove distracting color (cactus glochids).

|

|

Emphasize color (arnica flowers).

|

Abstract photography lets us post-process guilt-free ... so experiment!

|

Cropped, saturation (color) reduced, definition increased – all in iPhoto.

|

One of the more interesting techniques I came across was blown highlights – over-exposing to the point where all detail is lost in light areas. Ben Brain demonstrates how, shooting a vase of delphinium flowers in front of a brightly-lit window, using slow shutter speeds to “let the light flood in.”

|

| From delphiniums by Ben Brain. |

I used a similar approach in photographing bamboo against a pale wall. I adjusted exposure compensation up three stops – enough to erase all details in light areas – and ended up with a painting-like image of stems and leaves.

Highlights also can be blown quite effectively in

iPhoto. I created my own delphinium abstract from a photo taken in the wild, by adjusting the black and white sliders below the histogram, thereby darkening the dark tones and lightening the light ones. (Here's a

clear and useful article about improving images with the

iPhoto histogram, from

MacWorld.)

|

| Delphiniums (larkspurs) in the abstract ... |

|

| ... and in the wild. |

Even after all this analysis, I still struggle to explain why abstract photography is so appealing. Perhaps it’s the perfect mix of familiar and new, expected and unexpected. I certainly enjoy the opportunities to experiment and learn. The new worlds revealed by details are enchanting, and beauty in relatively simple images fascinates me. Discovery, beauty, creativity, fun … all are irresistible.